Editor’s Note:

Gold has long functioned as a hedge against inflation, instability, and monetary uncertainty. In this Vuepoint, Morton Lane suggests the price of gold can also serve as a real-time market barometer of confidence in U.S. economic stewardship.

The U.S. economy currently outperforms most of the G7 on conventional measures of growth and employment. Yet gold has risen sharply. Lane argues that gold often reflects not present conditions, but expectations about inflation, fiscal discipline, and central bank credibility. Markets, in this sense, may render their judgment long before economists do.

Gold as Political Barometer

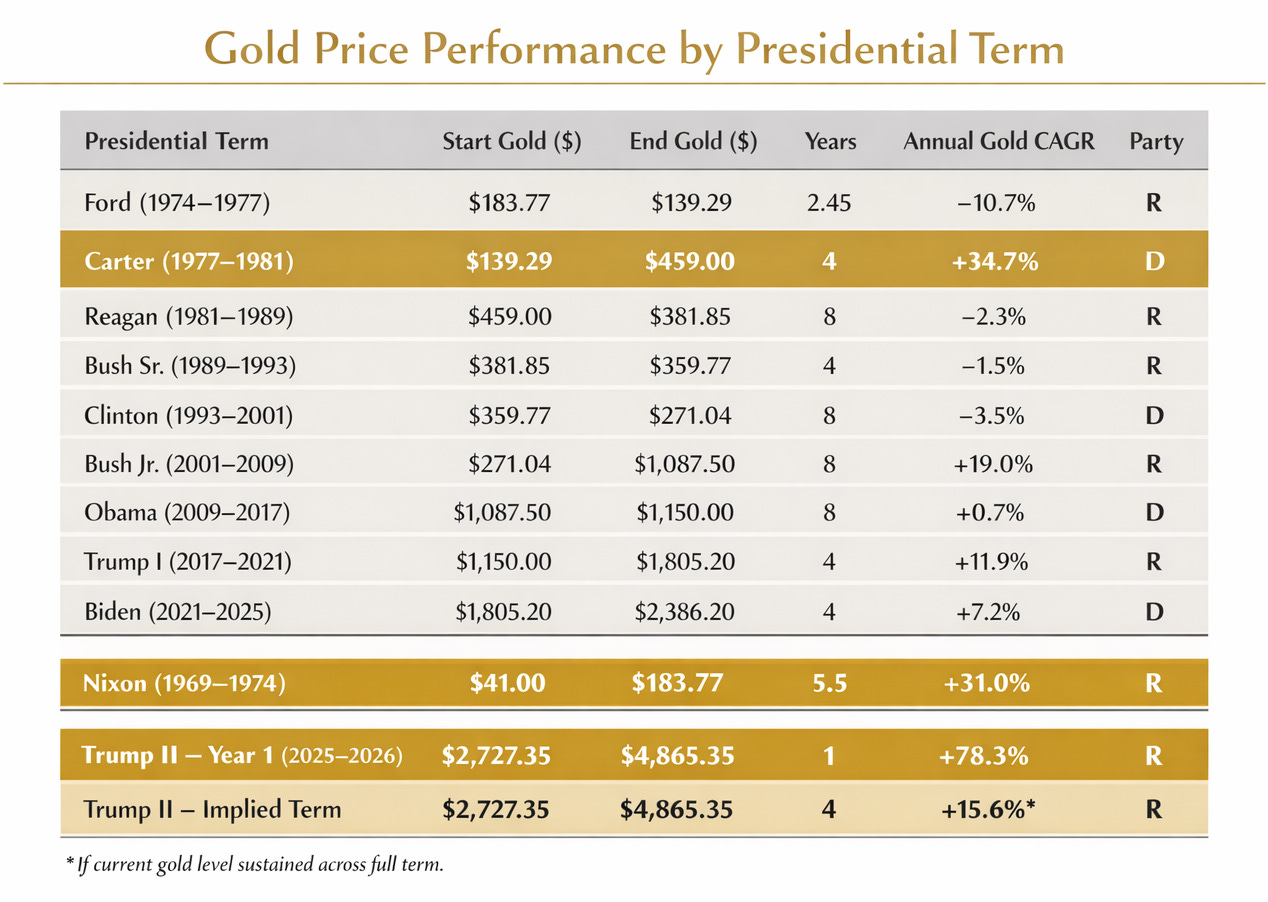

On the first anniversary of his second term in office, President Donald J. Trump saw the price of an ounce of gold at $4,865.35 — a 78.3% increase since Inauguration Day. Such a massive rise puts him in the company of Presidents Richard Nixon and Jimmy Carter.

The comparison is not to the double-digit consumer inflation of the 1970s, but to the rate of gold’s appreciation against the dollar — historically a sensitive indicator of market concern about future inflation, currency stability, and policy credibility.

As noted last year, I believe that the change in the price of gold over the duration of an individual presidential term provides a useful proxy for the ranking of each president’s stewardship of the world’s largest economy — the United States. Falling gold prices signal contentment with financial and fiscal affairs; dramatically rising gold prices signal the opposite — alarm. The voters in this drama are the collective will of the gold-holding world, and they vote with their pocketbooks by buying or selling gold, whether they be governments, corporations, criminals, or the honest saver on the street.

❝ Gold does not vote in elections — but it votes every day in markets.

To be in the company of Nixon and Carter, who each saw annual compound growth rates in the price of gold of over 30% on their watch (see table below) is a distinction to be avoided. Leaving aside the obvious personality parallels among these combative presidencies, the market is perhaps all too clearly seeing similarities between the Nixon and Trump monetary eras.

Gold’s annualized performance has historically surged during periods of monetary stress or policy uncertainty:

Nixon, Carter — and the Gold Warning Signal

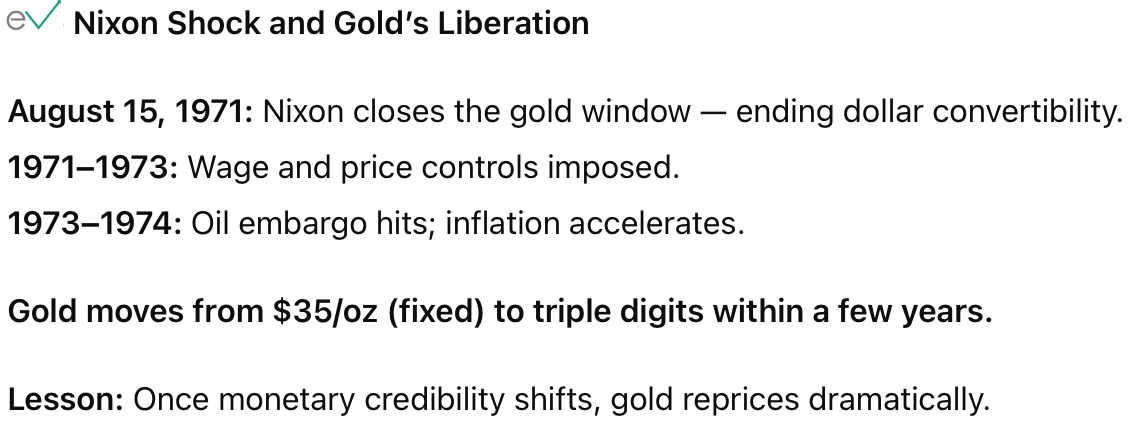

Memorably, Nixon inherited a guns and butter dilemma from the Vietnam War and then the first oil embargo in 1973. His instinct was to accommodate rather than restrain. He replaced William McChesney Martin Jr. as Federal Reserve Chair. Martin, who had served under Truman, Eisenhower, Kennedy, and Johnson, saw it as his job “to take away the punch bowl if the party got too hot.”

Nixon replaced Martin with Arthur Burns in 1970 and, if anything, Burns’s job became to keep the punch bowl firmly in place. As a result, Nixon:

a) was forced to take the U.S. off its quasi-gold standard,

b) kept interest rates relatively low, and

c) when inflation surged, imposed price controls to little effect.

❝ We are all Keynesians now. Richard Nixon, 1971

His successor, President Gerald Ford, tried to contain inflation by issuing WIN (“Whip Inflation Now”) buttons, to much derision in the button-loving trading pits of Chicago.

Burns’s term ended two years after President Carter was elected. Carter replaced him with G. William Miller, who proved equally ineffectual; worse, inflation had turned to stagflation. Carter, at one point, fired most of his cabinet in a major reshuffle, and Miller was moved to Treasury. Carter then replaced Miller with Paul Volcker. It was too little and too late to remove the inflationary tarnish from Carter’s presidency. Volcker, however, knew what to do — he took away the punch bowl, slamming on the economy’s brakes by raising interest rates dramatically. Volcker’s tenure ultimately spanned both the Ronald Reagan and George H. W. Bush presidencies.

Trump and the Return of Inflation Anxiety

The Trump presidency echoes much of Nixon’s. The first Trump term was beset by the Covid pandemic, not unlike Nixon’s oil embargo in terms of its economic shock. Trump and the Federal Reserve acceded to easy money to avoid an economic crash.

Inflation surged in 2021 following the extraordinary fiscal and monetary stimulus deployed during the pandemic. The Biden presidency began in 2021 amid this already expansionary fiscal environment and continued large-scale support programs; inflation pressures persisted before peaking in 2022.

This time, however, Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell — appointed by Trump in 2018 — reversed course in 2022 and tightened monetary conditions to prevent sustained inflation from the continued Covid stimulus. Inflation peaked but abated only slowly. By the time Trump began his second term, inflation remained above the Fed’s self-imposed 2% target.

If the Nixon shock was to take the United States off the gold standard, the Trump-2 shock was “Liberation Day” — the imposition of tariffs on friend and foe who allegedly “took advantage” of the United States. Tariffs added incremental price pressures for U.S. consumers, reinforcing a broader affordability squeeze driven primarily by housing, energy, and interest rates.

Circular Tariffs in History

By November 2025, Trump, like Nixon with his price controls, was already tinkering with some 200 tariff rollbacks on cocoa, bananas, and other goods. He is also mooting subsidies for farmers and a proposed “$2,000 tariff dividend” for citizens. A recent Supreme Court ruling found that the president cannot unilaterally impose tariffs under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA), removing one of the administration’s most flexible tools for rapid tariff action.

Other legal pathways remain available, including Section 232 national-security tariffs, Section 301 unfair-trade measures, and the recently announced maximum 15% increase allowed under the Section 122 tariff authority. However, the ruling introduces new uncertainty around the durability and fiscal use of tariff-derived revenues.

Using tariff revenues to fund consumer rebates risks a circular fiscal maneuver: returning to households funds that higher import prices have already extracted. History offers several examples of highly visible but ultimately symbolic responses to inflationary pressure: the Ford administration’s WIN (“Whip Inflation Now”) campaign of the 1970s, Nixon’s temporary wage and price controls, and, in more populist contexts, Evita Perón’s public redistribution through her Fundación. Such measures generated political visibility, but they did not substitute for durable monetary stabilization.

While not exactly price controls, these actions suggest a more interventionist economic posture — not on the scale of Beijing or Moscow, but a notable departure from traditional U.S. market orthodoxy.

The Fed Factor: Markets Are Watching

Reinforcing all of this is speculation around the replacement for Jerome Powell–Kevin Warsh–and whether he will prove to be a Burns-like figure rather than a Volcker-like one. After touching $5,000 per ounce, how much higher gold goes will depend on how seriously the next Fed Chair takes the inflation mandate.

In the days following the inauguration anniversary, gold jumped a further 10% to $5,500, but following Trump’s announcement of Kevin Warsh as his Fed Chair nominee, it has retreated back to the $5,000 level. The market clearly feels some relief. It could have been worse. But only time will tell whether Warsh resists political pressure and avoids a return to a Nixon-era inflationary cycle.

Of course, not all of gold’s recent rise can be attributed solely to U.S. policy. Central bank buying, particularly by China and other non-Western reserve managers, has accelerated since the freezing of Russian reserves in 2022. Gold is increasingly viewed as a neutral reserve asset in a more fragmented geopolitical system. Even so, as issuer of the world’s reserve currency, the United States remains the primary reference point for global monetary confidence, and gold continues to reflect market judgments about that credibility.

Conclusion: The Market’s Report Card

None of this necessarily implies that the U.S. economy is presently weak. By many conventional measures, it remains the strongest among the G7. Gold, however, does not primarily track current growth; it tracks confidence in future monetary and fiscal stability. For that reason, its rise may signal less a judgment on present performance than a hedge against future policy risk. Markets express that hedge continuously through the price of gold.

Watch gold to see how investors are evaluating the Trump presidency and, more broadly, the credibility of U.S. economic leadership, at least until the present incumbent earns his own gold watch.

About the Author: Morton Lane

Morton Lane is the retired Program Director of the Master of Science in Financial Engineering program at the University of Illinois. He writes occasional commentaries on current affairs and on one of his longstanding professional interests, the insurance-linked securities market. Prior to joining the University of Illinois, he ran an independent consultancy specializing in catastrophe reinsurance securitization.

Earlier in his career, Lane served as president of Discount Corporation of New York Futures, a brokerage that expanded alongside the rapid growth of financial derivatives markets, including U.S. Treasury bill and Treasury bond futures and options. At the outset of his career, he was part of a small team managing investments in the Treasury Department of the World Bank.

He has edited and co-authored several books, including The Treasury Bond Basis, Eurodollar Futures, and Alternative (Re)Insurance Strategies, as well as a volume reflecting another longstanding passion: mountaineering.

Lane continues to follow closely the markets in which he has spent his career. His recent essays blend market perspective with historical reflection on the evolution of modern finance.

📍Chicago