MEXICO 2020: econVue Special Report

Proposed Tax Reforms: Impacts on Investors & the Domestic Economy

Executive Summary

To create greater transparency and fairness in global corporate taxation, the OECD and the G20 have recommended that their members, including Mexico, implement Base Erosion and Profit Sharing (BEPS) taxation guidelines. As a result, Mexico is proposing to implement changes to Section XXXII of Article 28 of the Income Tax Law (MITL) as part of its 2020 Budget discussions now pending before Congress. If approved, these changes would result in reduced deductibility of interest expenses for businesses, the key subject of this report.

This new tax regime would result in increased costs and complexity for investors, particularly in manufacturing, where financing is required to build and maintain new facilities, but where jobs are created. Mexico is already widely considered to have a complex taxation regime, consistently ranking in the top ten globally1. In a world where companies have choices about where to invest, burdensome tax structures can add significantly to costs, making the difference between a feasible investment and one that is unprofitable or never takes place. New regulations tend to create uncertainty, which also hamper economic growth.

As companies with existing debt in their Mexican business are aware, there are three factors that must be considered when determining the net tax effect of interest expense under Mexican law. These are: income tax withholding, which is calculated on the nominal interest expense; the unrealized foreign exchange gain or loss against the Mexican peso; and the inflationary adjustment calculated on a legal entity ́s net payable or receivable position.

In Mexico’s case, non-deductibility of interest rate expenses net of inflation is especially onerous, due to the country’s higher than average inflation rate of about 3.5% versus an average of 1.9% for all OECD countries.2

If for example, interest is 10%, and inflation is 3.5%, only 6.5% will be deemed a deductible expense. The newly proposed regulations would introduce an additional interest deductibility limit of an inflationary adjustment AND 30% on gross EBITDA. So, the inflation adjustment would be made not just once, but increasing the exclusion for the same reason, twice. An additional problem is that annual inflation can be estimated, but can fluctuate, adding uncertainty--in this case double uncertainty--to the corporate budgeting process.

Markets themselves impose a third tax, as assets and investments are diminished in value by the inflation rate alone. Therefore, superimposing deductibility limits based on inflation twice, in addition to the natural effects of inflation, actually results in triple taxation.

We further discuss why the existing thin capitalization rule, which is meant to favor equity over debt, is not necessary in a country such as Mexico that already has low debt levels. With the implementation of Action 4 of the OECD’s BEPS program, the country’s investment environment will deteriorate because of the de facto increase in the investment costs. This new regulation would in fact make Mexico a less attractive destination for Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) compared to similar countries, with a resulting negative effect on employment. While it is difficult to calculate prospective losses to employment, there is no doubt that less investment in manufacturing will result in less employment. The manufacturing sector in Mexico is already experiencing a severe decline.

We discuss this pending change in the context of the special characteristics of the Mexican economy. This is a special time in its history, when as a result of US-China trade tensions, global supply chains are now in flux. Mexico has many advantages in addition to its proximity to the world’s largest economy and its imminent regional trading agreement with the US and Canada. These advantages could be diminished by excessive taxation.

Finally, even in the European Union, where BEPS was implemented beginning in 2016, it appears that it has failed to spur economic activity. It is estimated that they might have caused investment to have fallen by 5%.3 The United States only recently began to limit the deductibility of interest rate expenses. Without clear-cut success, there is simply not a long enough track record of lowering business interest expenses to undertake this policy. Theory and history suggest that this is more likely to lead to weaker growth.

It is important to note that certain classes of investments, specifically infrastructure and energy projects, will be exempted. BlackRock and other institutions are actively seeking investments in these sectors. Manufacturing and infrastructure investments go hand in hand. Allowing one to develop without the other—as has happened in the US, hampers both. Perhaps the solution is to also offer a similar exemption to manufacturers.

If these regulations are passed, Mexican and foreign companies with operations and investments in Mexico should review their forecasted ATI, Net Interest Expense, and comparison with thin capitalization rules, to be prepared for the impact of the proposed limitation on deductibility of interest expenses going forward.

About This Report

We became interested in exploring a proposed 2020 tax policy change in Mexico that could negatively affect investor sentiment--in spite of improvements in Mexico’s overall attractiveness as a destination for FDI. We researched the ramifications of implementation of the new policy for current and future investments, based upon implementation of the OECD’s Base Erosion and Profit Sharing (BEPS) plan. If enacted, tax deductibility of interest payments would be limited next year. This will affect companies that have already made long-term investment decisions based on previous financing assumptions, as well as those planning future investments. BEPS has other regressive outcomes as well, but for purposes of this report, we will focus solely on interest expense deductibility for businesses and suggest policy alternatives.

Information was gathered from a variety of sources, including the OECD, government and academic research, the international financial press, businesses with operations in Mexico, brokerage reports, as well as interviews with Mexican economists, legal experts, officials, bankers, and businesspeople. We analyzed and challenged the assumptions behind the implementation of the new tax regulations in light of the unique characteristics of the Mexico’s economy. We are confident of opportunities for growth, and the prosperity of Mexico’s people, if long- term incentives are aligned for the government and domestic and foreign investors. Public-private partnerships must benefit both sides and be sustainable.

The builders of businesses who are also job creators are by nature risk-takers. Successful nations find ways to mitigate those risks in order to benefit many others. Clearly what might seem like a small change could have longer-term negative consequences. Our purpose is to bring our findings to the attention of policymakers and investors in Mexico.

EconVue is not a registered investment or tax advisory; we are a consultancy that analyzes the economic effects of policy choices and geopolitical risks.

The Big Picture:

Mexico and the Global Economy

In the 1990’s the world entered a period of unparalleled prosperity. Driven by new advances in informational technology, living standards rose sharply, as millions were lifted out of poverty. The “end of history” was declared, but the pundits were premature, and conflicts returned. The downsides of globalization became apparent. Crowded cities, environmental degradation, and displacement of workers as global supply chains shifted—all were some of the negative changes as we moved into the 21st century. Then, the Global Financial Crisis arrived in 2007, and many began to wonder if we were moving too fast and leaving too many behind.

Political economists are trying to construct new theories of the nation-state under globalization, in a world where money, information, technology, and people transcend borders. Yet being completely open to the world has its downsides and is not the optimal model for economic growth. Just the right amount of openness and protection of the local economy yields the greatest success. This new paradigm is called technoglobalism.4 Generally speaking, openness to capital flows is an essential ingredient, as capital brings more than just money; it brings expertise and access to technology.

As Mexico enters a new era, its Fourth Transformation, it too must find this balance. What works for the developed countries of the OECD is not necessarily right for emerging economies. In fact, in our discussions we found that there was concern among these countries that these specific OECD tax reforms might not be one size fits all, given their wide divergence of size, structure and stage of economic development.

Mexico currently faces economic challenges. Social spending exceeds investment. In spite of slowing growth, and a primary budget surplus, the government is exercising procyclical fiscal restraint. Both actions will likely continue to slow GDP growth, which was 2% in 2018, but is expected to drop to .5% in 2019.5

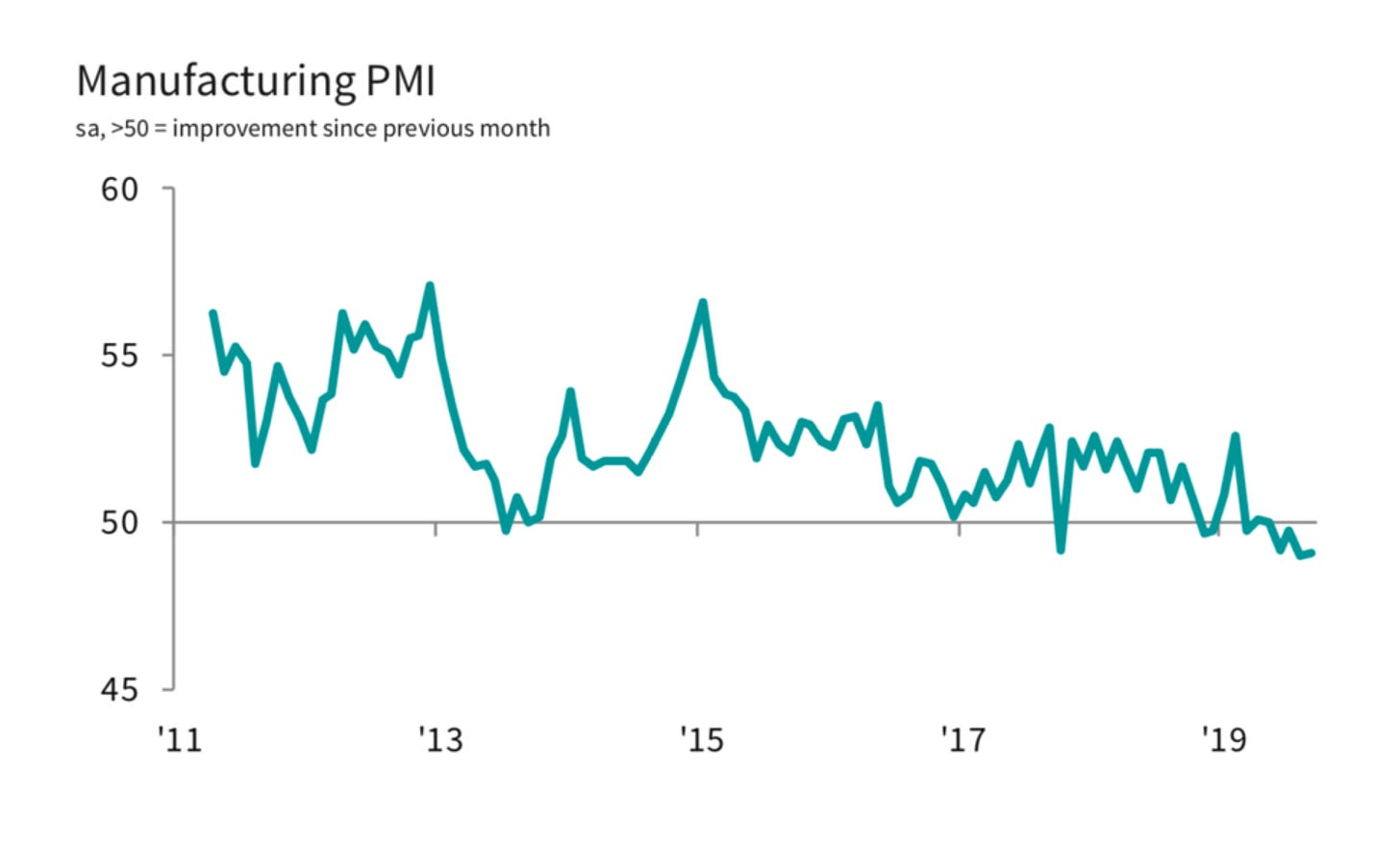

Manufacturing has taken a hit.

Commenting on recent disappointing PMI data, Pollyanna De Lima, principal economist at IHS Markit said:

"Mexico ended the third quarter of 2019 with its worst manufacturing performance in the eight-and-a-half-year survey history, owing to a record deterioration in business conditions in August and a broadly similar performance in September. Another month of weak order inflows kept production levels firmly in contraction, with the fall in output the fastest in the survey history. In response, manufacturers cut their staffing numbers again and further reduced purchasing activity. The downturn was often attributed to challenging economic conditions, weak demand and subdued client confidence. Meanwhile, prices charged were broadly stable as goods producers sought to stimulate demand by absorbing cost increases. Input cost inflation picked up to a nine-month high in September, largely due to peso weakness.6

Mexico is also exceptional in terms of the reliance of its economy, especially for employment, on manufacturing. Nearly 50% of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) is in manufacturing.

According the United Nations 2019 world investment report:

Mexico is one of the emerging countries most open to foreign direct investment (FDI) and the world’s fifteenth largest FDI recipient. FDI flows to the country fluctuate strongly depending on the arrival and departure of large international groups. In 2018, FDI inflows edged down to USD 31.6 billion, from USD 32.1 billion a year earlier. While flows remained comparable to levels seen in the last five years, they were considerably below the all-time high of USD 48.5 billion in 2013.7

FDI INFLOWS BY COUNTRY AND INDUSTRY8

OECD BEPS Action 4 = Double Taxation

Mexico has a lower tax-GDP ratio than all other members of the OECD, just 16.2% compared to an average of 34.2%. The BEPS initiative seeks to create a competitive tax system that improves both employment and investment, allowing the government to provide essential social services. However, Mexico is highly dependent on corporate taxation, due in part to the fact that its informal economy is by definition undertaxed at the level of the individual Social Security contributions are exactly half the OECD average, yet Mexico ranks #1 in corporate taxation, nearly 2 1⁄2 times average.9

This situation is likely to worsen with the adoption of new limitations for interest rate deduction set to go into effect next year if current legislation is approved (See page 9 for international comparisons).

The Executive branch of Mexico’s federal government presented the 2020 Budget to Congress on September 8th. The House of Representatives has until October 20th to approve the Budget, and the House and Senate until October 31st to approve the final Budget. The proposed changes include an alignment of Mexican tax law with the OECD’s BEPS initiative. Specifically, limitations will be place on interest deductibility. The Budget proposes a new test whereby the interest, net of the inflation adjustment, will be limited to 30% of the entity’s adjusted taxable income. The excess would carry forward for three years. The proposed law includes exceptions for infrastructure projects and an exemption for the initial MXN $20,000,000 of annual interest expense. Mexico 2020 tax reform includes several provisions addressing various BEPS concerns.10

According to an article in MNE Tax “Under the new rules, net interest in excess of the amount resulting from multiplying net income by 30% is not deductible. The reform provides a de-minimis exclusion of the first 20 million MXN pesos (approx. USD 1 million). The nondeductible excess can be carried forward for the next three years.”11

This is in addition to the following rules regarding thin capitalization, which results in double taxation, as explained by Deloitte:

Thin capitalization – Interest payments made by a Mexican resident company on a loan from a nonresident related party are nondeductible for income tax purposes to the extent the debt-to-equity ratio of the payer company exceeds 3:1. Debts incurred for the construction, operation or maintenance of productive infrastructure linked to strategic areas, or for the generation of electricity, are excluded from the application of the thin capitalization rules.12

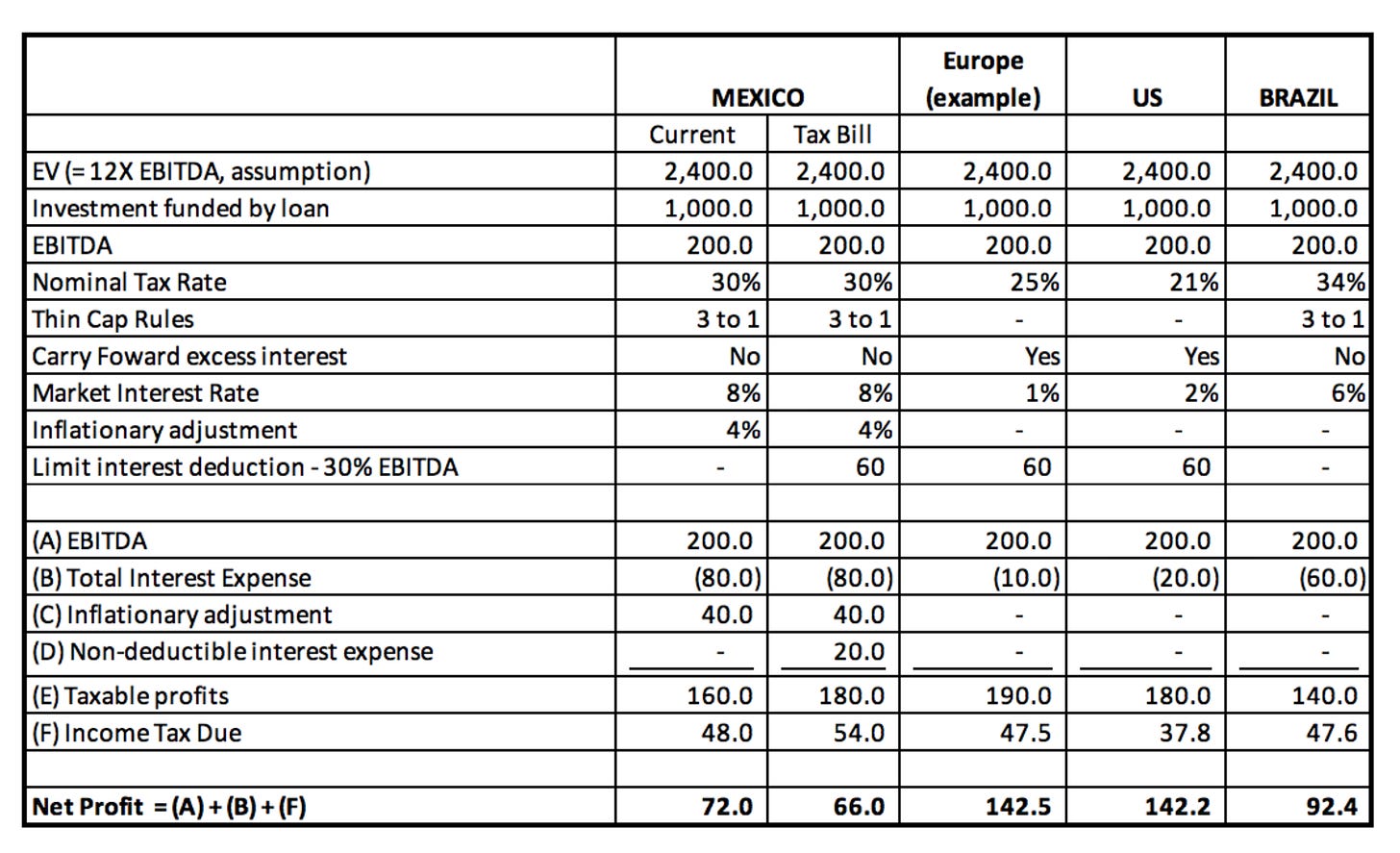

Here is a real-life before and after estimate of how the new BEPS tax structure would affect corporate taxes. Taxable profits would increase by 12.5% which also means that net profits would decrease.

Net profits in Mexico in this illustration are already low by comparison with Europe, the US and Brazil. This new tax regime would bring them even lower.

According to industry sources and experts, in addition to the existing thin capitalization rules, companies would now need to calculate a second limitation and apply the more punitive of the two limitations. The proposed rule would restrict a Mexican entity ́s net interest expense to 30% of the Mexican entity ́s adjusted taxable income, a version of income that is calculated similarly to EBITDA and described further below. Notably, inflationary income related to the underlying debt, foreign exchange gain or loss, and withholding tax would not be mitigated when there is a resulting applicable limitation on the interest deduction.

Adjusted taxable income subject to the 30% limitation would be calculated as the Mexican entity ́s stand-alone taxable income net of profit-sharing expense and increased for deductible interest expense and deductible tax depreciation/amortization/pre-operating expenses (“ATI”). There is an MXN 20,000,000 (approximately USD $1 million) de minimis exception for deductible interest applicable on a Mexican group basis.

The excess of the Mexican entity ́s net interest expense over the 30% of ATI limitation would not be deductible. Under the proposal, the taxpayer could carry forward the excess non-deductible amount for the following three tax years.

The proposed limitation would apply to a net interest expense, including third party debt. The proposed legislation defines net interest expense in the following manner: accrued interest expense on all debts over the accrued interest income on all receivables (Net Interest Expense). Interest expense/income that is not, respectively, deductible or accruable should be excluded from this calculation.

An exception for debt incurred for certain strategic activities is exempted from this limitation in line with the exceptions that exist currently for the thin capitalization rule. Debt related to activities such as public infrastructure, construction projects, as well as exploration, extraction, transportation and the storage of hydrocarbons, among others are exempt. Existing loans are not grandfathered under the proposed rules.

As companies with existing debt in their Mexican business are aware, there are three factors that must be considered when determining the net tax effect of interest expense under Mexican law. These are: income tax withholding, which is calculated on the nominal interest expense; the unrealized foreign exchange gain or loss against the Mexican peso; and the inflationary adjustment calculated on a legal entity ́s net payable or receivable position.

Certain foreign exchange income or loss related to debt is excluded from the definition of interest for purposes of determining the Net Interest Expense. Applicable withholding tax would not be reduced due to any non- deductibility of the interest expense. Finally, the computation of inflationary income is not adjusted for the non- deductible interest limitation. For example, even if a portion of the interest expense is limited under this proposed rule, the taxpayer would still have to accrue 100% of the related inflationary income.

Debates about how BEPS might be applied internationally continue. According to Europe Economics, in a study of impacts of interest limitation rules on Belgium and the EU, a balance needs to be found between curbing tax avoidance and discouraging investment:

“There has been considerable international support across the G20 and other major OECD countries for the introduction of measures to eliminate (or, at least, curb) abusive/artificial tax avoidance strategies believed to be implemented by a number of global corporations. It is also evident, however, that these same countries wish to attract foreign direct investment to increase employment and growth and, as a consequence, improve their fiscal position by way of taxes collected from corporation tax itself and, especially, from taxes on employment paid both by the workforce and the corporation itself. Accordingly, there is an inevitable tension between the implementation of the BEPS outcomes and the impact upon the competitive tax framework and rates offered by each competing economy. It would be extremely surprising if the BEPS outcomes were to be enacted as tax law and, in particular, implemented by the tax authorities on a wholly consistent basis.”13

Not All Countries Are Created Equal: Mexican Exceptionalism

One of the main arguments for reducing the deductibility of corporate interest on taxes is to equalize the tax treatment of equity and debt. With interest deductible and equity-financed income not deductible, tax codes across the OECD typically appear to artificially raise the cost of equity vis-à-vis debt. Excessive debt can certainly be problematic and can lead to more intense downturns and weaker recoveries from recessions, which most of the advanced OECD economies have experienced over the last decade-plus. However, and importantly, severely limiting corporate interest deductibility at this time appears to be a suboptimal policy solution for Mexico, given current economic and structural conditions.

If the Mexican corporate sector were highly indebted relative to regional and OECD peers, it would provide a stronger argument for taking measures to reduce the incentive to increase debt, such as thin capitalization. However, there is not much evidence to indicate that Mexico is highly indebted relative to regional peers. According to Bank of International Settlements (BIS) data, credit to non-financial corporations as a share of GDP in Mexico in 2018 stood at just under 26% of GDP . This compares to around 90% in advanced economies, emerging economies, and the G20 as a whole. While discouraging additional leverage in much of the rest of the OECD has a certain logic to it, that logic does not appear to be relevant in Mexico at this time.14

Furthermore, assuming that a reduction of the deductibility of corporate interest payments will lead to new equity-based financing investment is problematic. First, and potentially most concerningly, venture capital investment in Mexico is in a nascent stage. While venture capital investment represents at least 2% of GDP in two dozen OECD countries based on the most recent available data from the OECD, according to Financier Worldwide.15 In Mexico venture capital represents only 0.02% of GDP.

In general, early stage equity investments are geared towards just a handful of industries in the US: Internet, health care, telecom, and software.16 Additionally, equity index capitalization of non-financial firms is typically dominated by goods-producing industries and technology firms, whereas they represent a distinct minority of employment in the US.17 Many of the firms that rely on equity financing are in knowledge-intensive industries, and Mexico, as it stands today, is not poised to have market dominance in such fields given that the share of adults with at least a bachelor’s degree or higher is much lower than in most OECD countries.18 A recent World Bank analysis found that the limited pool of potential IT employees in Mexico was a major constraint on the industry’s potential growth.19 Certainly, there is an argument to have educational policy be geared towards increasing bachelor’s degree attainment in STEM fields in the future, such that Mexico can fully benefit from greater equity financing in the economy, but reducing interest deductibility alone will not produce that outcome.

Given that the Mexican corporate sector does not appear to be overly indebted at this time, and that an equity financing boom does not appear to be on the immediate horizon, a reduction in corporate debt deductibility without an offset elsewhere means that the corporate sector is facing an effective tax increase—even if it is in the form of what some consider to be a loophole. Previous cross-country research from officials at Harvard University, PWC, and the World Bank found negative adverse impacts between higher effective corporate income tax rates and aggregate investment, FDI, and entrepreneurial activity.20

The effect is especially correlated with the manufacturing sector. Since a higher share of output in Mexico is concentrated in the manufacturing sector compared to other OECD countries, and foreign firms represent a disproportionately large share of manufacturing employment in Mexico, the Mexican economy is more vulnerable to negative impacts associated with the de facto tax hike than other OECD economies.

Additionally, the report found that higher effective corporate income tax rates are associated with a larger share of the economy being informal, which remains a major issue in Mexico specifically. Recent studies have found over half of Mexican workers are in the informal sector, which reduces the ability of the government to properly collect tax revenue.21

While the desire for the normalization of debt and equity financing has some logic to it in highly indebted, rich economies—even if the benefits accrue to larger companies at the expense of smaller companies—the potential costs to Mexico of dramatically reducing the corporate interest deduction are higher than average. This is because Mexico currently:

Does not have an overly indebted non-financial corporate sector

Has a higher than OECD average share of manufacturing employment

Has a persistently large informal sector

A less well-educated workforce compared to most OECD economies

Foreign investors can choose to invest elsewhere

Given that dramatically reducing corporate interest deductibility will likely have real costs and only uncertain rewards, other measures to improve the efficiency of the Mexican tax code and increase tax revenues appear justified at this time.

The Cost of Uncertainty

The OECD itself recognizes that uncertainty is a major factor affecting investment decisions. Taxation weighs more heavily on decisionmakers in Latin America than in any other region:

There is a significant difference with tax uncertainty having a more frequent impact on significant business decisions in the three regions; this is especially pronounced for LAC(Latin America and the Caribbean) where tax uncertainty having very frequent impacts on business decisions is also significantly higher than in the OECD.

Policy uncertainty in general can have a deleterious effect on investment. According to economist Steven Davis at the Booth School of Business at the University of Chicago:

A variety of studies find evidence that high (policy) uncertainty undermines economic performance by leading firms to delay or forego investments and hiring, by slowing productivity-enhancing factor reallocation, and by depressing consumption expenditures. This evidence points to a positive payoff in the form of stronger macroeconomic performance if policymakers can deliver greater predictability in the policy environment. A smaller literature finds that greater uncertainty causes households and firms to become less responsive on the margin to cuts in interest rates and taxes, in line with predictions of real options theory.22

Prof. Davis has created a newspaper-based economic policy index for Mexico, since 1996. New data, from 2017 to the present shows a moderation in concerns.

Missing the China Boat

Growth in emerging markets and developed markets has continued to diverge. In particular, what Goldman Sachs calls the China impulse that aided emerging market growth has begun to fade. This is largely because the mothership has begun to slow--in spite of the promise of the Belt & Road initiative. Countries such

as Mexico will need to follow new models and roads to prosperity.

Conflict in the US-China trade relationship has presented a once in a generation opportunity for Mexico to benefit from shifting supply chains. Speaking to the Financial Times, Rogelio Ramírez de la O, an independent economist, said the US Congress “has become more or less unified around the China issue . . . That means that companies that flew to China to invest and, in some instances, to manufacture in China and resell in the US, now have to have a very hard look at the fact this is a state policy now in the US and is going to remain”... Companies and economists concede it is early days. “I’m not hearing there is a massive move into Mexico yet, but Mexico is the natural recipient,” Mr Ramírez de la O said.

In another article in the LA Times, The US and China Got in a Trade War, And Mexico Walked Away Richer we hear what might be the start of a beautiful friendship:

Given Trump’s early attacks on Mexico for taking U.S. jobs, it’s an ironic turn to observers such as factory consultant Alan Russell, who has never seen such interest by U.S. companies in opening facilities south of the border in his 35 years in the industry “It’s a case of unintended consequences,” said Russell, chief executive of Tecma Group, an El Paso firm that helps companies open and run factories in Mexico. “Any company manufacturing in China has had a wake-up call.”

The US China Chamber in Shanghai, in a survey of its members say that 20% are considering moving capacity out of China. This is an opportunity for Mexico. The question is, what might get in the way?

Macroeconomic Outcomes: Possible Employment Effects

Multinational businesses play a major role in the Mexican economy, especially in the manufacturing sector. While there have been multinationals who have not consistently acted with sensitivity to local conditions, Mexican government data analyzed by the International Labor Organization has found that multinational firms offer many benefits to Mexican workers.23 Multinational Enterprises (MNE’s) employed over 1.2 million people in 2014, including over 900,000 in the manufacturing sector according the most recently published census. Additionally, MNE’s paid higher wages on average than purely domestic entities, with average income being over 30% higher in 2014. MNE’s are typically much older than purely domestic business units, indicating the long-term planned nature of foreign investments. Other Mexican government surveys estimated that multinational entities employed around 2.7 million people in recent years.

Thus, rules that reduce the attractiveness of investment, both on a reduced NPV of current investments as well as raising questions about the potential for additional midstream rule changes going forward, could have a negative impact on the Mexican economy, if MNEs deploy their investment capital elsewhere. For example, if multinational entities stop opening new establishments due to the new law, and concerns about future changes, and the production and administrative employees find work at prevailing wages for non-multinational entities, this represents a decline in income and profits sharing of around 2 and 4 billion pesos in a single year, with effects potentially compounding further over time and being exacerbated if domestic entities do not step into the breach and fewer people are employed overall.

There is a growing body of evidence that the importation of foreign know-how can provide long-run benefits to local businesses as well as from the direct benefits from the investment and higher prevailing wages as well. In a 2011 experiment, Indian textile firms that learned modern managerial practices saw their productivity rise 11%.More importantly, many of the benefits of these interventions persisted for a number of firms.24

A separate experiment with SMEs in Mexico found similar benefits for firms that accepted guidance on managerial best practices in terms of these firms experiencing faster growth and more robust profits.25 The ability to learn from and benefit from leading global brands can have long-run benefits to local economies as the knowledge diffuses and key innovations and best practices stick in business processes throughout the local economy.

Conclusion

As Winston Churchill once said, no nation has taxed itself into prosperity. Taxation policy can be a powerful tool to carry out both economic and social reforms. New forms of taxation must be used judiciously, in order to avoid the dreaded Laffer Curve, whereby increases in taxation actually diminish government revenues.

In the post-globalist era, there has been a wide divergence between developed and developing economies. In the interests of equality, the same rules cannot apply to both. The BEPS plan to increase taxation is sensitive to inflation rates, which are negative in the EU where this new tax was promulgated, but decidedly positive in Latin America. One size clearly does not fit all, and in fact, emerging market countries have expressed their concerns that the new tax scheme would support FDI. Should BEPS be implemented in Mexico in 2020, the answer is clearly no.

Because of the US-China trade tensions, Mexico has a unique opportunity to displace Chinese supply chains. Foreign Direct Investment brings many advantages beyond money-it brings technology and managerial know how. Infrastructure is a good public investment, but roads and bridges must go somewhere, and new power plants must be supported by business activity. Mexico has a large manufacturing sector that should be allowed to grow at the same rate as the infrastructure that supports it for maximum benefit to Mexico’s economy. This will ensure Mexico’s long-term competitiveness.

Retrograde motion is the apparent motion of a planet in a direction opposite to that of other bodies within its system, as observed from a particular vantage point. We believe that the preponderance of the research we have presented leads to the conclusion that adoption of the new tax regulations discussed in this report could have negative results, propelling Mexico in an unnecessary reverse direction, impacting the country’s economy, in ways that might prove difficult to reverse. Further study and consideration of the elimination of the inflation adjustment should be made before their adoption.

Gray, Stephen “Infrastructure Investment: Shifting the Focus from Cost to Opportunity.” Area Development. Q4 2018.

Ibata-Arens, Kathryn C. “Beyond Technonationalism: Biomedical Innovation and Entrepreneurship in Asia.” Stanford University Press. April 2019.

OECD cuts Mexico growth forecast to 1.6%.” El Universal. 03/05/2019.

https://www.eluniversal.com.mx/english/oecd-cuts-mexico-growth-forecast-16

IHS Markit Mexico Manufacturing PMI. October 2019.

https://www.markiteconomics.com/Public/Home/PressRelease/21460bb83d264e279a85277369eb4b79

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. “World Investment Report 2019.”

Santander. “Mexico: Foreign Investment.” September 2019.

https://en.portal.santandertrade.com/establish-overseas/mexico/foreign-investment

PwC “Mexico Budget 2020”, 9-09-2019.

Hernandez, Fernando J. “Mexico 2020 tax reform: big changes proposed for foreign companies doing business in Mexico” September 24, 2019.

Deloitte. “International Tax: Mexico Highlights.” 2019.

Europe Economics, “The Impact of Interest Deductibility Limitation Rules on Belgium and the European Union.” May 22, 2016.

Bank for International Settlements. “Total credit to non-financial corporations (core debt)”. 2019.

Financier Worldwide. “Venture Capital Transactions in Mexico.” March 2017.

https://www.financierworldwide.com/venture-capital-transactions-in-mexico#.XZjNEunQiuV

PriceWaterhouseCoopers. Moneytree Report, Q2 2019.

https://www.pwc.com/us/en/moneytree- report/assets/moneytree-report-q2-2019.pdf

Holodny, Elena. “A crystal clear illustration of how the stock market is not the US economy” Business Insider. October 28, 2015.

https://www.pwc.com/us/en/moneytree-report/assets/moneytree-report-q2- 2019.pdf

OECD. Percentage of adults who have attained tertiary education, by type of programme and age group (2015).

https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/education/education-at-a-glance-2016_eag-2016-en#page44

The World Bank. “Moving Toward a Knowledge-Based Economy: Improving Competitiveness in Mexico’s Information Technology Industry”. November 2017.

Djankov, et al. “The Effect of Corporate Taxes on Investment and Entrepreneurship.” NBER Working Paper Series. 2008.

International Labour Organization. “Informal Employment in Mexico: Current situation, policies, and challenges.” 2014.

Steven J Davis. “Rising Policy Uncertainty” Working Paper No. 2019-111. Becker Freidman Institute, University of Chicago. August 2019.

https://bfi.uchicago.edu/wp-content/uploads/BFI_WP_2019111-1.pdf

David Barstow & Alejandra Xanic von Bertrab. “How Wal-Mart Used Payoffs to Get Its Way in Mexico” New York Times. December 17, 2012.

https://www.nytimes.com/2012/12/18/business/walmart-bribes-teotihuacan.html

Bloom, et al. “Do Management Interventions Last? Evidence from India.” NBER Working Paper. 2018.

Smith, Noah. “Management Consultants Might Be the Best Foreign Aid.” Bloomberg Opinion. July 18, 2019.