The Financial Ring of Fire

How a crisis in Taiwan could spark a run on the US bond market

The Third Dimension of Taiwan Risk

Taiwan now holds roughly USD 1.7 trillion in foreign assets, including an estimated USD 700 billion in US securities, largely long-duration USD bonds held by life insurers1. Most analyses of a Chinese invasion of Taiwan focus on two channels: military confrontation and disruption to global trade, especially advanced semiconductors. But almost no one has fully considered the third, and potentially most dangerous, channel of risk: financial contagion2.

This omission is becoming increasingly dangerous. The newly released US National Security Strategy (NSS) reiterates that Taiwan is a core American national security priority. Yet within this broad strategic framework, one critical dimension remains unexplored: how a Taiwan emergency could trigger a global financial shock within hours, far more quickly than policymakers currently anticipate3.

The core risk is simple: Taiwan’s financial system is designed in a way that converts an exchange-rate move into forced selling of US bonds. No other major creditor nation exhibits this combination of size, fragility, and reflexivity.

How Taiwan Became a Creditor State

This blind spot exists because policymakers have not updated their perception of Taiwan’s financial footprint. In 1978, the year President Jimmy Carter normalized relations with Beijing, Taiwan was a struggling developing economy with a modest USD 15–20 billion in foreign assets4. An invasion or blockade then would have been a geopolitical crisis, but not a financial shock outside Taiwan.

That world no longer exists. Taiwan has quietly become one of the most influential and most misunderstood financial actors in the US bond market.

One Global Bond Market, Two Systemically Important Creditor States

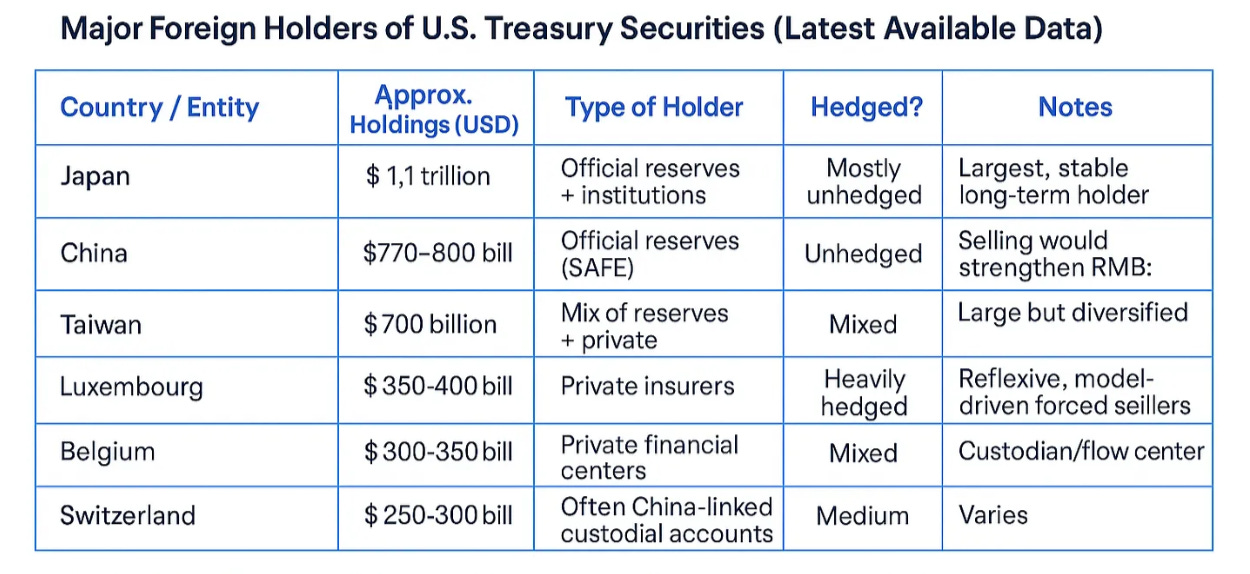

Over five decades, the Pacific has become home to several of the world’s great creditor states, each built on different foundations: Japan through household savings, China through its official reserves, Singapore through sovereign-led global finance, and Taiwan through high savings and insurer-driven foreign investment. All are major holders of long-duration US bonds.

Japan's and China’s positions are largely unhedged. Singapore’s sovereign-led foreign-asset structure behaves as a stabilizer, with none of Taiwan’s reflexivity, in part because its insurers hedge far less aggressively.

In the current atmosphere of heightened tensions between the US and China, it is tempting to assume that because China holds more US Treasuries than Taiwan, a rapid sell-off by Beijing would pose the greater threat to US financial stability. In reality, the opposite is true. China’s holdings are predominantly official reserves managed by SAFE5, unhedged, and not subject to automatic liquidation. Beijing has every incentive to unwind positions slowly and discreetly, as it has been doing, since sudden selling would strengthen the renminbi and damage China’s struggling export sector.

This stands in contrast to the popular “weaponized finance” debate surrounding China, which exaggerates Beijing’s incentive or ability to “dump” Treasuries. The real destabilizing channel lies elsewhere: Taiwan’s private-sector hedging architecture.

Taiwan’s Insurers, not China, are the Real Transmission Mechanism

Taiwan’s holdings are structurally different. Although large, its offshore bond holdings are highly concentrated in long-duration bonds, heavily hedged, and uniquely exposed to FX shocks6. Insurance companies, not the Central Bank of the Republic of China (CBC) hold most of the risk; Taiwan has no sovereign wealth fund to absorb volatility.

In a crisis involving a credible threat of kinetic conflict, Taiwan’s insurers face immediate FX losses, pressure to hedge, and, if the NTD moves sharply, forced selling of US Treasuries and corporate bonds. Every action they take would further amplify the crisis. Unlike China, which can choose when and how to sell, they are forced sellers.

Why Households and Corporates Don’t Pose Systemic Risk

Although Taiwanese households and corporates hold even more foreign assets than insurers, their behavior does not transmit stress to US bond markets7. In an emergency, retail investors generally hoard USD, but do not own significant long-duration bond portfolios.

Corporates behave similarly, accumulating USD for trade and overseas operations. Even TSMC, Taiwan’s most systemically important firm, keeps USD working capital in USD but does not hold long-duration Treasuries. In a crisis it would hoard dollars, not sell bonds.

These sectors may intensify Taiwan’s domestic liquidity stress, but they do not trigger forced selling in US fixed-income markets. Only the life insurers, because of their hedging structures and regulatory ratios, can convert an NTD shock into immediate selling pressure in the US Treasury market.

Taiwan’s private financial structure behaves less like a traditional creditor and more like a set of giant margin accounts, capable of transmitting a political shock from China directly into the US bond market.

This distinction is fundamental: retail and corporates may tighten liquidity at home, but only insurers transmit that stress abroad. If this is the key point of failure, the policy response must begin here.

How to Fix Insurer Portfolios - the Critical Weak Link

1. Gradually Reduce Hedge Ratios

Taiwan must move away from 70–95% hedging toward a more sustainable structure.

Lower hedge ratios = less mechanical forced selling.

2. Shorten Duration and Diversify

Shift from long-dated corporates and Treasuries toward shorter-duration assets and mixed FX exposure.

3. Create a Standing Repo Facility for Insurers

A CBC facility allowing insurers to repo U.S. bonds removes the need for fire-sale liquidation.

4. Allow Countercyclical Hedge Adjustments

During periods of abnormal volatility, relax hedge-ratio requirements to break the reflexive loop.

Taiwanese insurers are not unaware of these vulnerabilities—far from it. Their regulatory filings, RBC (capital adequacy) disclosures, and repeated interactions with the FSC (Financial Supervisory Commission) and foreign rating agencies show that they actively monitor hedge ratios, duration mismatches, and FX losses. The major firms—Cathay Life, Fubon Life, Nan Shan, Shin Kong, and Taiwan Life—regularly adjust portfolios in response to rising hedge costs, and have all shortened duration at various points over the past decade.

What has been less widely understood, both in Taipei and abroad, is the systemic implication: that these balance-sheet structures do not merely create domestic solvency pressures, but can transmit a Taiwan shock directly into the US Treasury market. The firms themselves manage the risks they see. What they have not been forced to confront is the global contagion channel their collective behavior can create.

The four measures we have recommended directly attack the mechanism that transmits Taiwan’s crisis into US markets. Some require action in Washington, others in Taipei, and some by the G7 collectively. None require formal treaty changes. But if insurance portfolios are the root cause of fragility, and the transmission channel, the exchange rate is the trigger. In a crisis, FX would behave counterintuitively.

Why a Taiwan Crisis Would Strengthen the Taiwan Dollar — Not Crash It

Most people assume that in a geopolitical crisis, the affected country’s currency collapses. In Taiwan’s case, the opposite is true — and this is one of the most dangerous and least understood mechanisms in global finance.

A Taiwan crisis would actually strengthen the New Taiwan Dollar, not weaken it. Because Taiwanese insurers hold roughly USD 700 billion in U.S. bonds that are heavily hedged, any sharp move in the NTD—especially appreciation—creates immediate hedging losses8. To cover these losses, insurers must sell US Treasuries and corporate bonds, receive US dollars, and then convert those dollars back into NTD to meet regulatory hedge ratios.

This mass repatriation creates intense buying pressure for the NTD, causing it to surge even higher. A stronger NTD then produces even larger hedging losses, triggering more forced selling and more repatriation in a self-reinforcing loop.

Over time however, if the crisis persists and economic fundamentals deteriorate, the NTD would eventually weaken—but by then the global shock triggered by the initial forced-selling would already have occurred.

How the Contagion Would Spread

How exactly would a Taiwan crisis send destabilizing shockwaves throughout the global financial system? The run on financial assets, spurred by market signals and intelligence, would precede a military strike. Markets will move faster than a speeding missile.

What makes this dynamic especially destabilizing is that global markets would interpret Taiwan’s forced selling not as a local liquidity event but as a signal that Taiwanese institutions are reacting to imminent geopolitical risk. In an environment where algorithms and macro funds are trained to chase flows, the sudden liquidation of hundreds of billions in U.S. fixed-income assets would be read as a warning shot. This could trigger copycat de-risking by global investors, widening credit spreads, dumping duration, and amplifying volatility across asset classes long before any conflict materializes.

Contagion Timeline

To continue reading the full analysis and support our work, become a paid subscriber.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to econVue to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.