Xi Jinping's Long March

Struggle sessions continue as India charts its own path: A framework for understanding US-China relations

This article has been unlocked for our free subscribers. We invite you to consider becoming a paid subscriber to access all econVue content—20% off forever! ♦

Early in 2022, I believed that China’s economy would recover slowly, but I did not predict that the current slump would last this long. I underestimated the brittleness of Chinese policymaking, rooted more in politics and dogma than in the principles of economics.

China was once the driver of global growth. Now there is little doubt that its economy is slowing. We just don’t know how much and how fast, because reliable data is getting harder to find. It sometimes even contradicts itself, as Council on Foreign Relations trade economist Brad Setser explains:

Is China's external surplus small and receding (as the IMF argues) or large and if anything growing as China relies on exports to offset its real estate downturn?There is no consensus, in large part because important data sets diverge.1

A New Long March in the Wrong Direction

If China is heading in the wrong direction in terms of economic policy, there is no reason for competitors to celebrate. Much depends on Washington’s response to Beijing, while India is poised to benefit either way. The US should lead, not follow, in order to successfully adapt to a multipolar 21st century. However, in both countries, political considerations tend to outweigh economic issues which are poorly understood. We might be seeing overcapacity in tradable goods, but there is definitely undercapacity in leadership in both countries able to understand how trade, and the global economy work.

China’s current path is reminiscent of ill-begotten Mao-era measures which massacred sparrows and turned farm and cooking implements into micro steel smelters. The result was famine for tens of millions. Is Xi Jinping leading China on a new Long March to a more insular, uncertain, and less prosperous future?

Observers looking for new fiscal stimulus coming out of the Third Plenum in July were disappointed.2 It seems the time for the cash handouts which worked in the US has passed.3 And no relief was granted to assist purchasers cheated by real estate developers, inaction justified by government concern over moral hazard. The problem however was caused by property developers, many of whom have already been punished. Buyers had reason to believe that it is the government’s job is to regulate illegal behavior and protect its citizens.

In fact, the structural issues that spurred massive overdevelopment in the property sector were always under the control of the central government. Cities and provinces, starved of tax revenue, naively resorted to investment in real estate, with a predictable result: a massive bubble that has destroyed billions of dollars of assets.

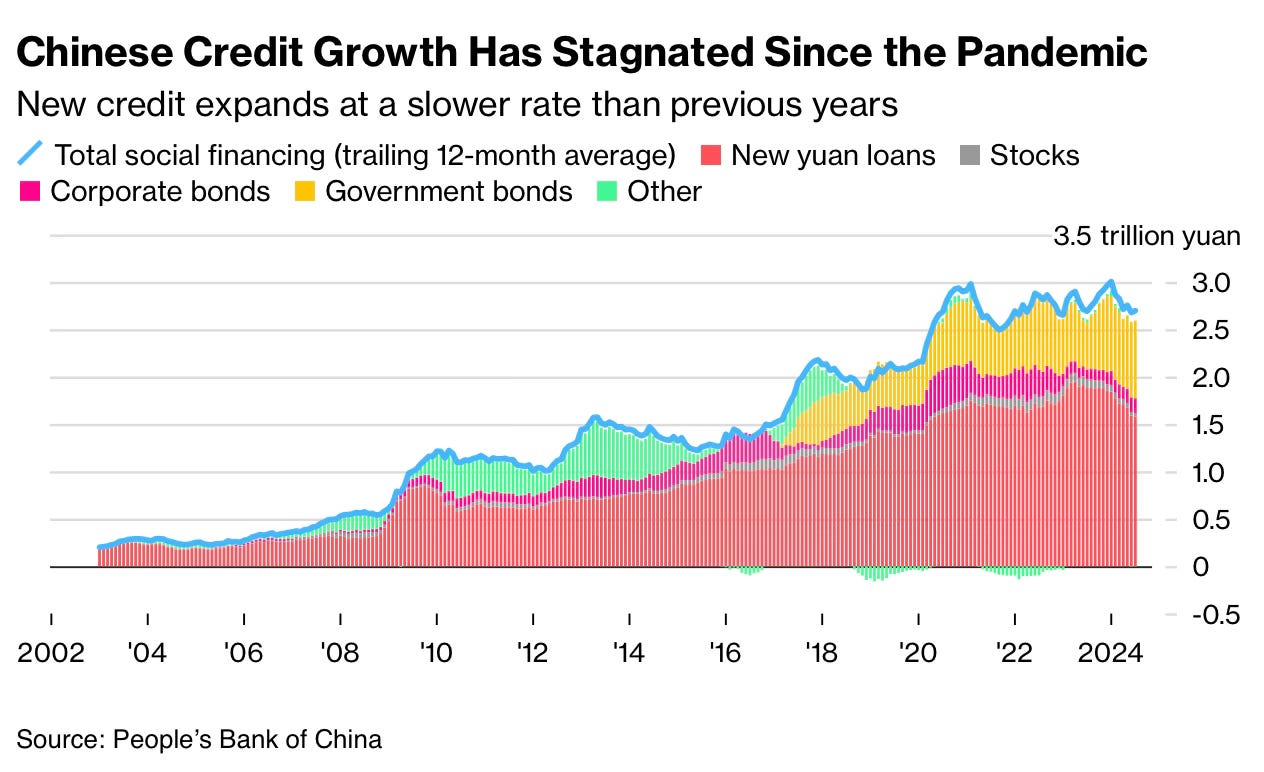

Another signpost of China’s slowing economy is credit growth, which has not been responsive to lower interest rates. Bank lending has continued to weaken, resulting in a fall in fixed asset investment. 4

Geopolitical Headwinds

China’s economic slowdown is welcomed by many in the US. Anti-China rhetoric and legislation has unprecedented bipartisan support in a presidential election year with very few points of agreement. Soon, a raft of new China legislation and regulation will be enacted that will further limit China’s ability to maneuver in the US, and by extension, in the world economy.

A 45-year old science and technology pact negotiated by Jimmy Carter and Deng Xiaoping, is due to renew next month after a six-month extension, but its fate is uncertain and raises questions about the US-China relationship overall. Is this outcome and increasing lack of cooperation beneficial or detrimental? Will China’s continued economic weakness become a new source of contagion? Since no leadership change is on the horizon in China, how do the US and the G7 control for or minimize the consequences of Xi’s detrimental policies?

Did you know…⧉

⧉ Mao Zedong: Approximately 33 years in power (1943-1976) → age 82⧉ Xi Jinping: Approximately 11 years in power (2012-present) age 71China’s participation in global trade increased rapidly after joining the WTO in 2001. Exports quadrupled, while imports tripled. China played a neat trick, simultaneously contributing to global growth, while lowering inflation. The cost for the US was 2.7 million jobs lost between 2001 and 2011, and lasting political fallout.

Meanwhile, infrastructure building in China increased demand for commodities worldwide, including in the BRI (Xi’s Belt & Road Initiative) countries it has financed since 2013. Manufacturing and supply chains in China significantly lowered the costs of many goods, and its own middle class expanded.

Today, trade winds have shifted based on the slowdown within China. Countries reliant on Chinese demand, such as Australia and Brazil, are likely to see declines. China is facing financial constraints internally, just as its BRI partners are confronting massive debt overhangs that accelerated during the pandemic, and later ballooned in a much higher interest rate environment.

China’s 21st century tragedy is that its leaders did not use its moment of prosperity and global goodwill to bridge the temporary losses required to enact institutional reforms. Japan was relatively rich before its stagnation began, but that is not the case with China. Instead, since 2012 its leadership has doubled down on the Sovietization of its economy, and the bellicosity of its foreign policy.

The Road from Partner to Competitor

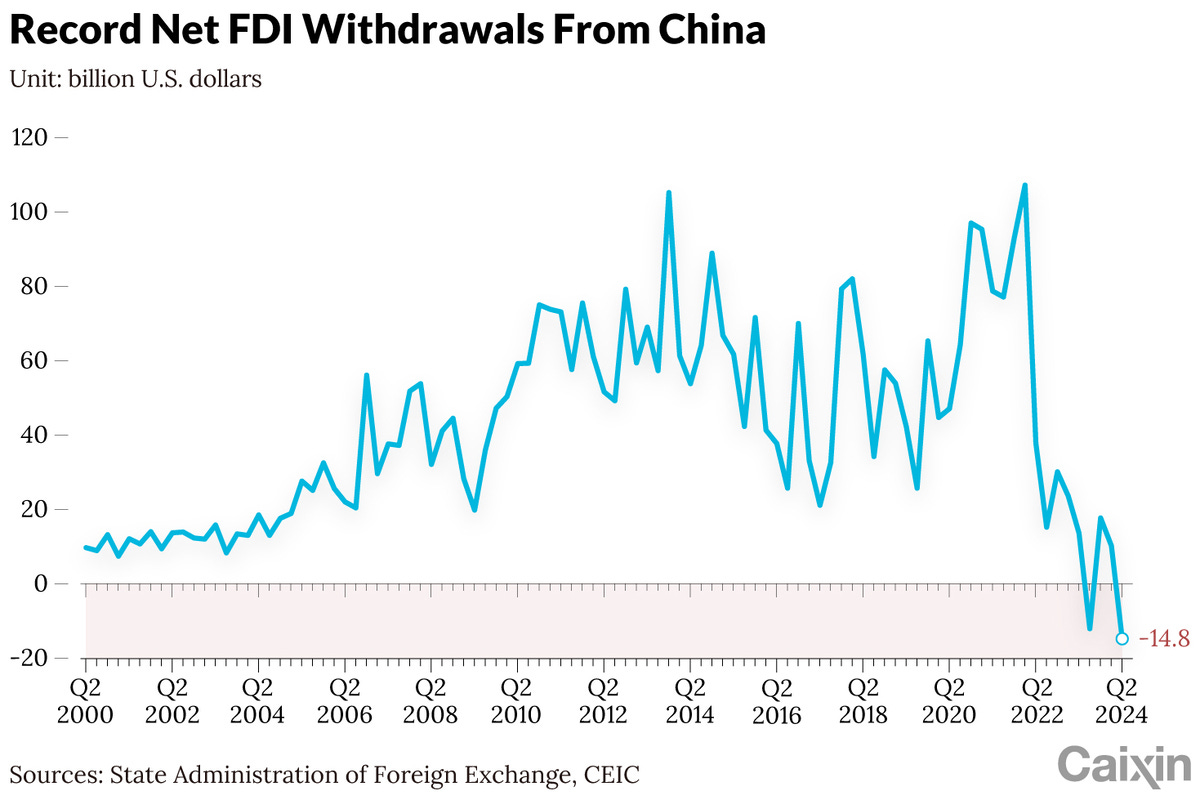

Although much of what is wrong with the Chinese economy is self-inflicted, it is also the victim of its own success. FDI, a key growth driver has plummeted. This is a critical metric because FDI is not just about money; it is also about know-how.

Supply chains are now geopolitical tools. Both FDI and foreign technology, the building blocks of China’s prosperity, have found new homes in South Asia and North America. Instead of being a source of growth, China could become the locus of slowing global economy.

The reason most often given for this trend is that investors in China, assessing geopolitical risk, have decided to diversify. But there is another intriguing possibility. Foreign firms no longer able to compete profitably in the Chinese market might be using geopolitical tensions as an excuse to withdraw and head for the exits.

To be fair to foreign firms doing business in China, they have also become fatigued with regulatory uncertainty and overreach, and a procurement system that advantages “national champions” regardless of the quality of the goods they produce. Criminalizing data flows and periodic boycotts did not help investor sentiment either. Overall, since domestic demand is weak, China is a less attractive market than it was during the boom days.

China’s Overcapacity “Doom Loop”

Chinese consumption has failed to rally after the pandemic, so current production levels exceed internal demand. Domestic consumers have failed to rally around various buying campaigns in a world where social services are no longer free. Jobs are much scarcer especially for young people who should be the center of household formation. Demographic headwinds are gathering strength in spite of the end of the one-child policy. China has long prized industrial production over services as the visible marker of economic progress and is turning sharply to global markets in its search for growth.

But there is a more enduring driver of the present stasis, one that runs deeper than Xi’s growing authoritarianism or the effects of a crashing property market: a decades-old economic strategy that privileges industrial production over all else, an approach that, over time, has resulted in enormous structural overcapacity…Simply put, in many crucial economic sectors, China is producing far more output than it, or foreign markets, can sustainably absorb. As a result, the Chinese economy runs the risk of getting caught in a doom loop of falling prices, insolvency, factory closures, and, ultimately, job losses.5

Zongyuan Zoe Liu, Foreign Affairs, Sep/Oct 2024

This situation reminds me of The Trouble with Tribbles. In an episode of the original Star Trek TV series, a space trader brings a few fuzzy creatures onboard the US Enterprise, and suddenly the entire ship is overrun. The situation is resolved when the Scotty, ship engineer transports them all to an enemy starship.

Global Response

It should be noted that China does not agree that is producing at a rate that exceeds demand. Others disagree, not only in developed countries, but in developing economies. “Chinese firms are already feasting on demand that would otherwise be met by local manufacturers.” Princeton political scientist Aaron Friedberg says a collective strategy, a federation response, is the only way to stem China’s mercantilism.6 How can this be accomplished when the WTO itself is ineffective? Friedberg suggests a brand new trade defense coalition, combined security concerns with trade issues.

What exactly does overcapacity mean for the global economy? Aren’t cheap goods, even if subsidized by the producer’s government, a good thing? Not really, because China, still a member of the WTO, risks retaliatory action by attempting to grow its way out of its economic mistakes in EV’s, batteries, and solar panels by flooding world markets. It also damages China’s perceived position and moral high ground in a rules-based world order.

For decades China has acknowledged at different times that overcapacity (产能过剩) is an issue to be addressed in specific sectors. Overcapacity is related but not identical to typical trade concepts of dumping or macroeconomic concepts of balances…even before former president Donald Trump’s trade war, 7% or $100B of China’s exports to G20 economies faced antidumping or related trade restrictions.7

Martin Chorzempa, PIIE Jul 25, 2024

In past episodes of industrial overcapacity in China, the government had full control of its state-owned companies. The coal industry is a good example. Beginning in 2016 the government set a target of closing 1000 mines, as part of broader supply-side structural reforms, at a cost of $15 billion and many hundreds of thousands of jobs, improving air quality along the way.

What is different about this time is that the companies that are engaged in hyper production are largely private, not state-owned like many of the coal companies. The government does not have direct control over their production.

Goldman Sachs has said that Chinese overcapacity will not persist, and they even see a path to profitability. However, several industries, solar, EVs, batteries, semiconductors, construction machinery, and steel are now locked in a fierce price war.

The View From Inside China

Although it is easy to understand how and why China and Chinese companies are trying to export their way out of their financial difficulties and maximize profit, Chinese media is reporting on how trading partners are reacting.

Amid a prolonged real estate downturn and lukewarm domestic consumption, exports have once again emerged as a key driver of China’s economic growth. However, the surge in overseas shipments is a double-edged sword, as it has sparked retaliation among China’s trading partners concerned about protecting their own domestic industries and intensified simmering political frictions with the U.S. and Europe.

In the first half of 2024, net exports of goods and services contributed 13.9% to China's economic growth, boosting GDP by 0.7 percentage points — a stark contrast to the negative 11.4% contribution seen in 2023, according to the National Bureau of Statistics.8

Wang Liwei et al, Caixin, Aug 12, 2024

Here we can clearly see the inherent contradiction in China’s approach to international relations. The country seeks to be a world leader while internally it adheres to ideologically driven policies that undermine its own economic growth and global influence. This creates domestic tensions as well as conflict with other countries.

This dilemma is downright Hegelian. What is the synthesis of these two opposing ideas, and inevitable resolution? Since it is unlikely the world will change, the hope is that these tensions, internal and external, could eventually lead to internal reforms of its economic system. Otherwise, clashes will continue. Contributing to climate change for example through China’s environmentally friendly products will not outweigh economic damage to local players. Because politics is local.

Root Causes

Overcapacity has become hardwired into the Chinese system. There are many causes, among them:

Short term profits are favored over long-term gains

As short-termism permeates throughout the society, everyone and every investment crowds into the favored sectors of the current administration, or the sectors that brings immediate results and immediate profit. To conclude, overcapacity has been a constant feature of the Chinese economy over the last forty years, and it is a result of the operating environment. Until we see environmental change in China, overcapacity will always be there.

Desmond Shum on X (author of Red Roulette)

I especially like this explanation because it belies the common belief among casual observers that China somehow is different than other societies, and that they are able to take the long view.

Domestic competition is fierce

A larger problem with China’s reliance on local government to implement industrial policy is that it causes cities and regions across the country to compete in the same sectors rather than complement each other or play to their own strengths.

Zoe Liu in Foreign Affairs

Another little understood feature of the local landscape. When I first visited China and attended the Canton Trade Fair, each province had its own exhibit. Many industries were duplicated in province after province, rather than the regional specialization I expected to see. This fragmentation mirrors the political system itself which rewards local accomplishments, as the basis for central government advancement, and so it persists today.

The end of a decades long cycle

Coming to the end of this long cycle, the evolution of China’s manufacturing process reminds me of the agave plant, which can survive under harsh conditions for as long as a century. At the end of its life, it grows a flowering stalk, which can reach a height of 20-30 feet in order to attract pollinators. After it blooms spectacularly this one time, it usually dies, although the offshoots at its base can create new plants.

China’s surge in exports might be following a similar pattern. Absent young labor, the ability to attract international talent and money, with increasing restrictions on technological transfer imposed by the US and its allies, a near-certain increase in tariffs in the next six months, and facing comparatively high energy costs and significant regional competition, it is hard to envision a near-term renaissance of Chinese manufacturing.

Crucially, the future of manufacturing is in AI and China has been limited in this area of technological advancement due to geopolitical tensions, materials sanctions, and its own self-imposed limits on data usage. But as Elon Musk and others have pointed out, China excels in infrastructure construction, high speed rail, and did remarkably well manufacturing electric vehicles and dominating the market in an incredibly short period of time. Perhaps the answer lies in specialization, but China’s security concerns will lead it to continue on its current path.

Strategic Competition with the US

The Trump tariffs on Chinese imports have remained in place under President Biden. Since their inception in 2018, tariffs have raised approximately $80 billion in revenues for the US government.

The Biden Administration took a different approach, which has been costly in the short term, and which has seen significant delays in execution. The CHIPS Act is estimated to cost $280 billion over the next ten years, and the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) will cost $437 billion over the same period. Both contain provisions aimed at reducing US dependence on China, maintaining US technological and industrial leadership. 9

There are broader implications for the global economy of this two-pronged approach comprised of tariffs and competition in the guise of industrial policy, that we will not be able to accurately assess for many years.

It is important to note that China is not a monolith, and not everyone in China agrees with the approach now being taken by Xi Jinping. Many would agree with my critique of China’s economic policies. They have concerns about the future of US-China relations under either presidential candidate.

Many members of China’s professional and business elite feel despair about the state of relations with the United States. They know that China benefits more by being integrated into the Western-led global system than by being excluded from it. But if Washington sticks to its current path and continues to head toward a trade war, it may inadvertently cause Beijing to double down on the industrial policies that are causing overcapacity in the first place. In the long run, this would be as bad for the West as it would be for China.

Zoe Liu, Foreign Affairs

The unintended consequences of US-led industrial policy that is focused on competing with China, which has a failing system, is that the US overshoots and disrupts its own economy.

India’s Favorable Tailwinds

The US-China trading relationship does not exists in a vacuum—there are many other players. As South Asia in particular rises, pushed forward by favorable demographic tailwinds, China faces new competition in its own region.

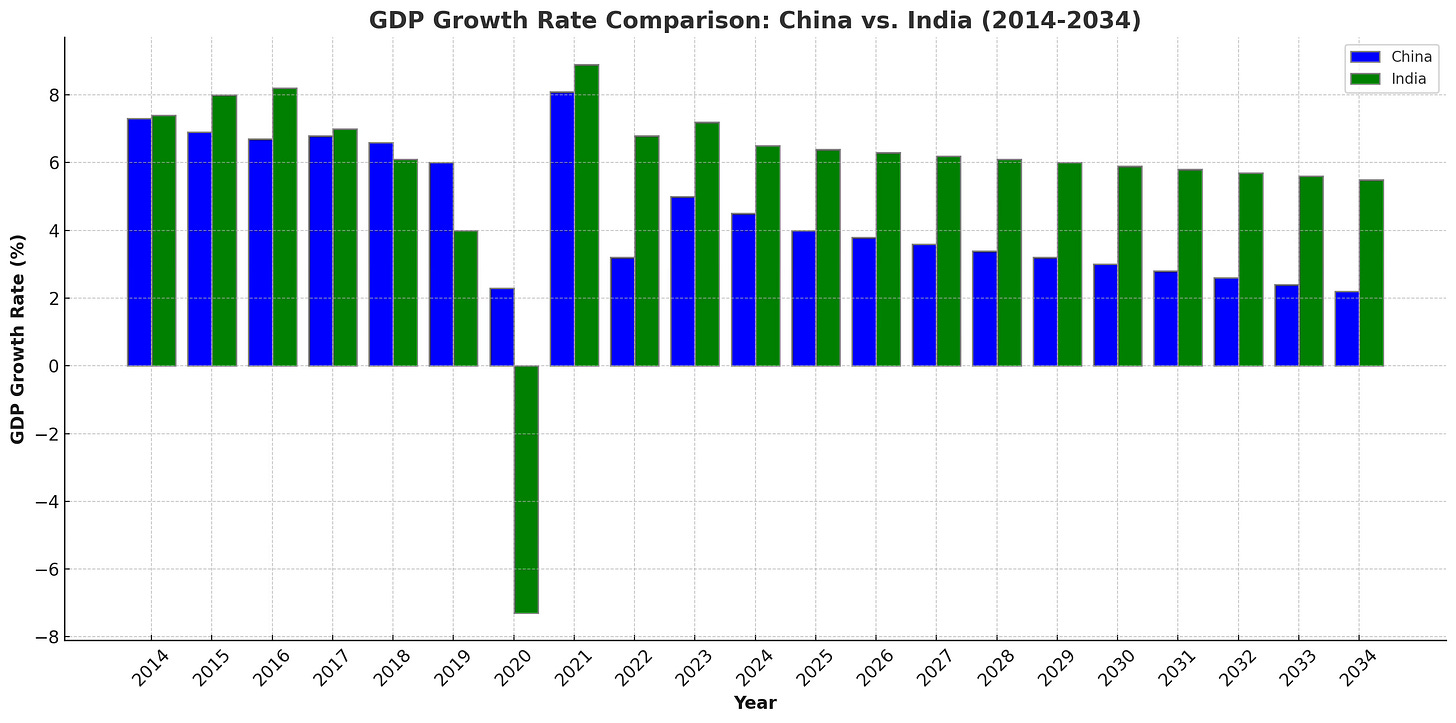

India is an economy with immense potential to fill the gap left by China's slowdown, but with significant challenges to overcome. While China’s growth rate has fallen, India’s has momentum. While India might not yet be able to fully replace China in terms of its contribution to global growth, it has been adroit at positioning itself as a country able to do business with all of the great powers, despite geopolitical tensions.

India is by no means a manufacturing powerhouse, but with a growing population, it has room to expand, while China’s labor force has already peaked. However, Chinese overproduction threatens to stall manufacturing development not just in India, but throughout the region.

More on India-China comparisons later, and a future panel discussion for our subscribers. But It is useful to contrast a very large country that manufactures too much with one that makes too little, and imagine what the future might bring as AI takes hold and the human labor force matters less. Which country will benefit most from this trend?

Another less-discussed factor is that although India’s own infrastructure is still developing, it is simultaneously becoming an indispensable regional hub for all of South Asia.

Over the past decade, India has built deep linkages in four key areas — finance, supply chains, petroleum, and (power and road) infrastructure. These investments have now emerged as stabilizing factors during a political crisis.

Gokul Sahni on X, Aug 20, 2024

A Crash Ahead?

India has serious disputes over its border with Pakistan, and with Bangladesh over water rights, but the country is more generally at peace with its neighbors than China. China is involved in disputes with at least ten of its neighbors including India, which sometimes break out in conflict, as recent skirmishes in the Philippines attest. And of course, China is the source of the granddaddy of all territorial disputes, with Taiwan. These territorial and maritime disagreements represent serious risks not just to the regional but to the entire global economy.

Watch for an all-out attack on these lesser targets before the main event in the Taiwan Strait begins.

My somewhat serious suggestion is that it might benefit the world if China made peace with Indian border claims and then help India build out an environmentally-friendly infrastructure. According to IQAir India currently has 9 out of 10 of the world’s most polluted cities. Yesterday, China approved 11 new nuclear reactors. But human factors prevent this rational approach.

⧉

→ The Long March

⧉ The Long March (1934-35) was a foundational event in modern Chinese history, and crucial in solidifying Mao Zedong’s leadership in the CCP.

⧉ There were multiple long marches, and they indeed were long and full of hardships, approximately 6000-8000 miles.

⧉ The Long March began as a strategic retreat from Jiangxi Province after the Red Army suffered heavy losses fighting the Kuomintang’s (Nationalist Party) Encirclement Campaigns. It is a textbook case of guerrilla warfare.

⧉ Women played a key role, including Li Zhen, one of China’s first female generals. Fathers & Sons and the Long March of History

A few observations about the human and historical factors interwoven with the US-China relationship.

Both George W. Bush and Xi Jinping have something in common that has had broad impact on their respective countries. Both are sons of famous leaders, and might have perceived failures in the actions of their fathers, which they attempted to remedy during their own successful political careers. It is likely for example that George W. Bush’s decision not to invade Iraq was seen by his son as a contributing factor to terrorist attacks on US soil on 9/11, and led to the invasion of Iraq in 2003 without direct justification.

Xi Jinping’s father Xi Zhongxun was a Long Marcher, but he was also a critic and occasional outcast of the Chinese Communist Party. Rather than his father’s more pragmatic approach to economic liberalization, Xi seems to have doubled down on adherence to Marxist principles.

This is all the more surprising, since his father, who was governor of Guangdong Province from 1978-1980, is widely thought to be the architect of Southern China’s economic miracle, including the expansion of Shenzhen from a fishing village to a huge metropolis, and the creation of China’s first Special Economic Zones, or SEZ’s. In other words, Xi’s father, based on Deng Xiaoping’s directives, opened China up to the West.

His son seems to regret those actions in part, but is there really any turning back for China? In a world which is so highly interconnected, the question remains whether China can isolate itself ideologically, and continue to live long and prosper in the global economy.

Conclusions

China’s Waning Influence: If China continues to prioritize ideology over economic pragmatism, as happened under Mao, Xi’s modern Long March will lead his country into a future that is less prosperous, and China will gradually become less of a contributor to global growth as its population shrinks. India has already exceeded it in this regard.

Global Risks: The US should think twice about welcoming China’s latest self-inflicted economic challenges, which could be destabilizing not just within China, but for the rest of the world. Disruptions in global supply chains and for commodity producers could have spillover effects in other economies, and on the global financial system now straining under unprecedented debt.

India’s Potential: As China’s influence wanes, India has emerged as a potential new engine of global growth. However, India’s ability to fully replace China will depend on its success in addressing internal challenges, such as infrastructure deficits and regulatory hurdles. India’s strategic positioning as a partner to multiple global powers could be a key advantage, allowing it to fill the gap left by China’s slowdown, becoming a regional hub for South Asia.

Future Outlook: After decades of depending on China as the world’s growth engine, the rest of the world should be ready for a global economy less dominated by China and the US, and more multipolar in nature. Leadership challenges in both countries could hasten this process of lessening influence.

Roadblocks

US China policy, which is unlikely to change after the presidential election, is wrongly focused on strategic competition with China, which is unwilling to adapt to the realities of this new world. Both are following a path that will lead to success for neither.

Similarly, there are no signs that Chinese leadership is willing to re-engage in reforms that were halted beginning in 2012 when Xi Jinping came into power. The speed and direction of Xi Jinping’s new Long March will determine whether or not China and a reactive rather than proactive US are left behind on world’s road to economic progress. ♦

Lyric Hughes Hale

Lyric Hughes Hale serves as Editor-in-Chief of Econvue, which publishes a newsletter, econVue+. She hosts The Hale Report, a podcast series on global economics. She is Director of Research at Hale Strategic

📍Chicago

China’s third plenum: watch what they do not what they say, David Lubin, Chatham House, Jul 22, 2024

Hey Google, Time to Add China ‘Koreafication to Your Search Engine, Malcolm Scott, Bloomberg, Aug 16, 2024.

China’s Real Economic Crisis: Why Beijing Won’t Give Up on a Failing Model, Zongyuan Zoe Liu, Foreign Affairs, Sep/Oct 2024

Stopping the Next China Shock: A Collective Strategy for Countering Beijing’s Mercantilism, Aaron L Friedberg, Foreign Affairs, Sep/Oct 2024

Fixing China’s trade imbalance needs a home remedy, Wang Liwei, Yu Hairong and Han Wei, Caixin, Aug 12, 2024

Delays hit 40% of Biden’s major IRA manufacturing projects, Amanda Chu, Alexandra White and Rhea Basarkar, Financial Times, Aug 11, 2024