After the Storm: China's Military Purges and the Rise of a Mobilization State

What the removal of Zhang Youxia and senior PLA leadership reveals about Beijing's shift from growth engine to a security-driven political economy

Editor’s note: Recent changes inside China’s military have prompted renewed debate about command authority, political control, and the country’s longer-term strategic trajectory. In this article, econVue contributor Eric Huang examines what the removal of senior People’s Liberation Army leadership may signal about China’s evolving political economy and its implications for global markets and geopolitics.

In the world of strategic intelligence, we often say that the most significant movements aren’t the ones that make the loudest noise, but the ones that change the frequency of the entire room. For years, the international community has viewed the periodic disappearances within the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) through a familiar lens of routine anti-corruption theater or another generic tiger caught in the net. But the fall of General Zhang Youxia, a man who until very recently was considered the untouchable anchor of the Chinese military establishment, may signal something far more profound. This is not just a personnel change. It may represent a fundamental recalibration of the risk calculus for the Taiwan Strait and the global geopolitical order.

❝ China’s political economy is shifting from a developmental model to a mobilization model in which security now outweighs prosperity.

On January 24, 2026, China’s Ministry of National Defense confirmed what had been rumored for weeks: General Zhang Youxia, the PLA’s senior vice chairman and Xi’s long-time confidant, along with General Liu Zhenli, face investigation for “serious violations of discipline and law.”1 This is no isolated scalp in Xi’s anti-corruption campaign; it appears to be the culmination of a sweep that has removed five of the seven Central Military Commission (CMC) members appointed at the 20th Party Congress. 2

The official confirmation that General Zhang Youxia and General Liu Zhenli have been placed under investigation is, for all intents and purposes, a self-inflicted decapitation strike against the PLA’s leadership structure. To understand the scale of this disruption, one must look at the numbers. Of the seven-man leadership team selected during the 20th Party Congress in 2022, five have now been purged. In less than three years, the core of the world’s largest standing military has been hollowed out from within by the very hand that appointed them. This is not a military in disarray, but a military being remade for a specific purpose. Xi is systematically dismantling the general-led military of the past and replacing it with a command-centric system. He is trading experience and prestige for absolute, frictionless vertical obedience.

Who Was Zhang Youxia—and Why His Fall Matters

To understand why this has sent a chill through regional capitals, we have to look at who Zhang Youxia actually was. He was not a technocrat or a logistics officer who could be easily replaced. Zhang was the ultimate Red Second Generation. His father, Zhang Zongxun, fought alongside Xi Jinping’s father, Xi Zhongxun, in the northwest battlefields. This was not just a professional relationship but a dynastic alliance. Zhang was the man who helped Xi consolidate his grip on a fractured military early in his tenure, serving as the bridge between the old guard and the new era. In a military that has not seen major combat since 1979, Zhang was also the rare “fighting general”. His tactical success during the 1984 Battle of Old Mountain gave him a level of operational credibility and institutional gravity that cannot be manufactured.

The historical relationship between the fathers of Zhang Youxia and Xi Jinping forms the bedrock of their long-standing “princeling” alliance, a bond forged in the fires of the Chinese Civil War. General Zhang Zongxun, a legendary figure in the People’s Liberation Army, and Xi Zhongxun, the reform-minded former Vice Premier, were both prominent natives of Weinan, Shaanxi Province, creating deep “hometown” ties that carry immense weight in elite Chinese politics. Their professional partnership reached a peak in 1947 when Zhang Zongxun served as the commander and Xi Zhongxun as the political commissar of the Northwest Field Army. This “Iron Triangle” of military and political coordination in the Shaanxi-Gansu-Ningxia border region was instrumental in defending the Communist heartland. Accounts often highlight how Zhang Zongxun’s military protection and unwavering loyalty provided a critical shield for the Xi family during various revolutionary purges, helping preserve the dynastic lineage that would eventually see their sons ascend to the pinnacle of power decades later.

Zhang Youxia represented the last prominent surviving princeling—hong er dai—in the upper echelons of power, where “princelings” (taizi dang) traditionally refer to those who pursued political careers rather than purely business paths. Xi Jinping has systematically ceased elevating fourth-generation princelings or allowing broader Red Second Generation networks to rise, effectively sidelining this once-influential group. Within the princeling circle, factions have long existed: an enlightened or reform-oriented wing contrasted with Xi’s more conservative, loyalist supporters. Xi’s closest princeling allies included Yu Zhengsheng and Wang Qishan—the latter instrumental in helping Xi consolidate power within the Party apparatus—while Zhang Youxia played the parallel role in securing Xi’s grip over the PLA. Unlike others who have been removed or marginalized, Zhang’s fall may mark the near-total eclipse of this dynastic cohort at the apex of Chinese power.

Yet that bond has evaporated into a cloud of rumors suggesting a high-stakes challenge to Xi’s authority. There are persistent reports that Zhang did not go quietly and that he may have led a faction of senior generals, including the now-purged Liu Zhenli, in a direct internal confrontation with Xi over the direction of the military and the handling of the economy. These are not just whispers of graft but allegations of a political clique that challenged the Chairman’s ultimate authority. Zhang did not just fall; he may have pushed back, possibly questioning the feasibility of Xi’s timeline for military readiness or the strategic cost of his aggressive posturing. While such claims remain difficult to verify, this internal friction was also reflected by a chillingly formal PLA communiqué, which demanded the “thorough eradication of the ‘poisonous influence’ of disloyal elements” and warned that any attempt to “undermine the Chairman Responsibility System” or “form political cliques” would be met with the full weight of Party discipline.3

The result is a military leadership that has been effectively hollowed out. Of the seven-man CMC appointed in 2022, only two remain: Xi Jinping himself and Zhang Shengmin, the military’s top discipline officer (the systems’s internal enforcer). This leaves the world’s largest military with an experience gap in an unusually concentrated command structure. Perhaps more startling is the broader political erasure. For the first time in the modern era, the uniformed military has been virtually stripped of its voice in the highest echelons of the Politburo. Xi is no longer negotiating with general-led power centers. He is presiding over a military that has been reduced to a subordinate administrative organ where the Chairman Responsibility System is now the only law that matters.

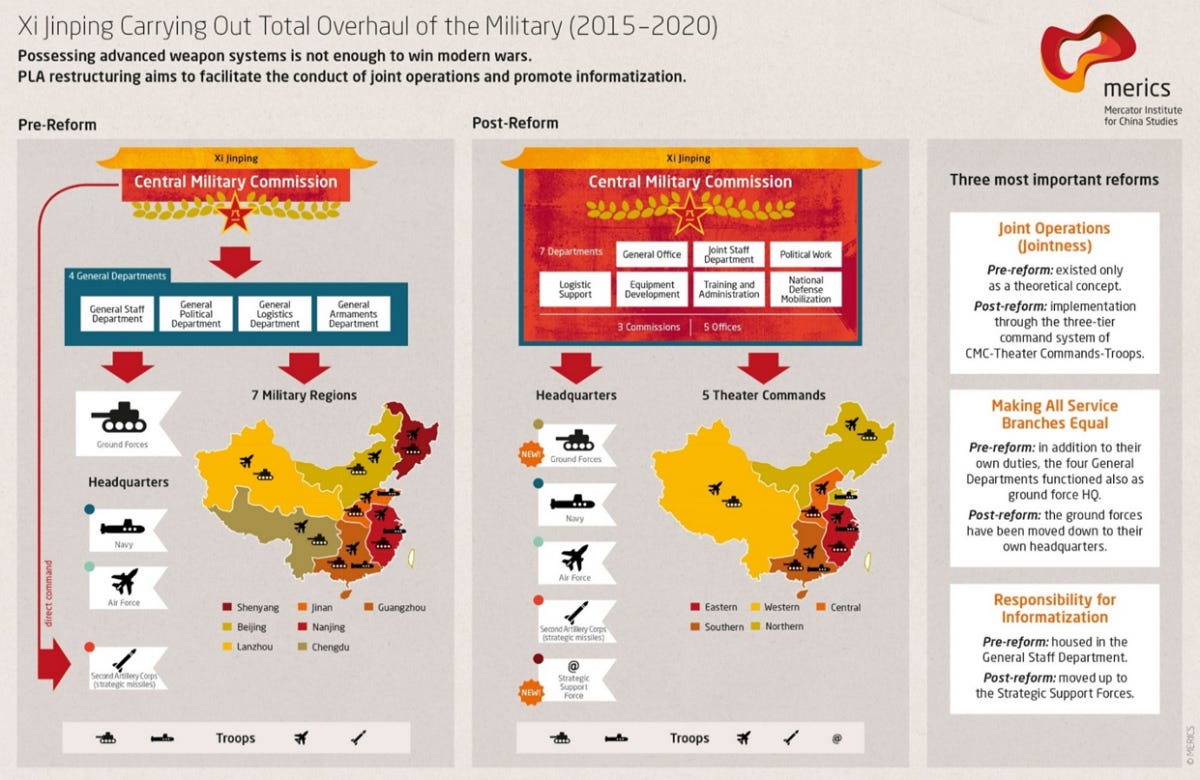

The 2015 Reforms: Separating Command from Administration

Xi Jinping’s campaign to subordinate the PLA began well before the current purges, most dramatically with the sweeping 2015-2016 military reforms. In late 2015, Xi abolished the PLA’s four powerful general departments (General Staff, General Political, General Logistics, and General Armaments)—long-dominant Army-centric bureaucracies that had functioned as semi-autonomous headquarters. These were replaced by 15 streamlined CMC departments, commissions, and offices, expanding central oversight and diluting any single entity’s independent authority. The seven Army-heavy military regions were disbanded and reorganized into five joint theater commands (戰區), which now focus on warfighting and operational command (指揮權). Theater commands bear responsibility for joint operations, while administrative functions—such as personnel management in peacetime—remain partially divided, with services emphasizing force-building (training, equipping) rather than direct operational control. This deliberate separation of command from administration centralized authority under the CMC Chairman while reducing risks of factional autonomy. Logistics and materials were further centralized under the new Joint Logistic Support Force, ensuring strategic supplies remain under tight CMC control rather than dispersed service silos. Critically, these changes stripped the PLA of any structural capacity to topple Xi or mount a coup: by dismantling entrenched power centers and enforcing a command-led system from the outset, Xi ensured the military could never again function as an independent political actor.4

Mission Command with Chinese Characteristics

Recent analysis from a RAND Corporation report suggests that elements within the PLA are experimenting with elements of “mission command” (任務性指揮)—a more decentralized, flexible approach inspired by U.S. military doctrine, where superiors issue broad intent and subordinates exercise initiative and adaptability in execution. Traditionally influenced by Soviet-style rigid, top-down command, the PLA has long suffered from micromanagement, limited lower-level initiative, and vulnerability to degraded communications in contested environments. According to the report’s co-author Nathan Beauchamp-Mustafaga, PLA reformers advocate for greater decentralization to enable quicker decision-making, better resilience against U.S. strikes on command nodes, and improved joint operations performance.5 Recent exercises have shown upper echelons issuing principles while allowing tactical flexibility below, though Party control remains firm and unyielding. This push for partial “mission command with Chinese characteristics” could enhance PLA agility in high-intensity conflict, but it risks inconsistent implementation, potential over-aggression from self-interested lower commanders without tight central oversight, or hybrid failures that combine the worst of centralized rigidity and decentralized chaos—especially amid ongoing purges that prioritize loyalty over operational experience.

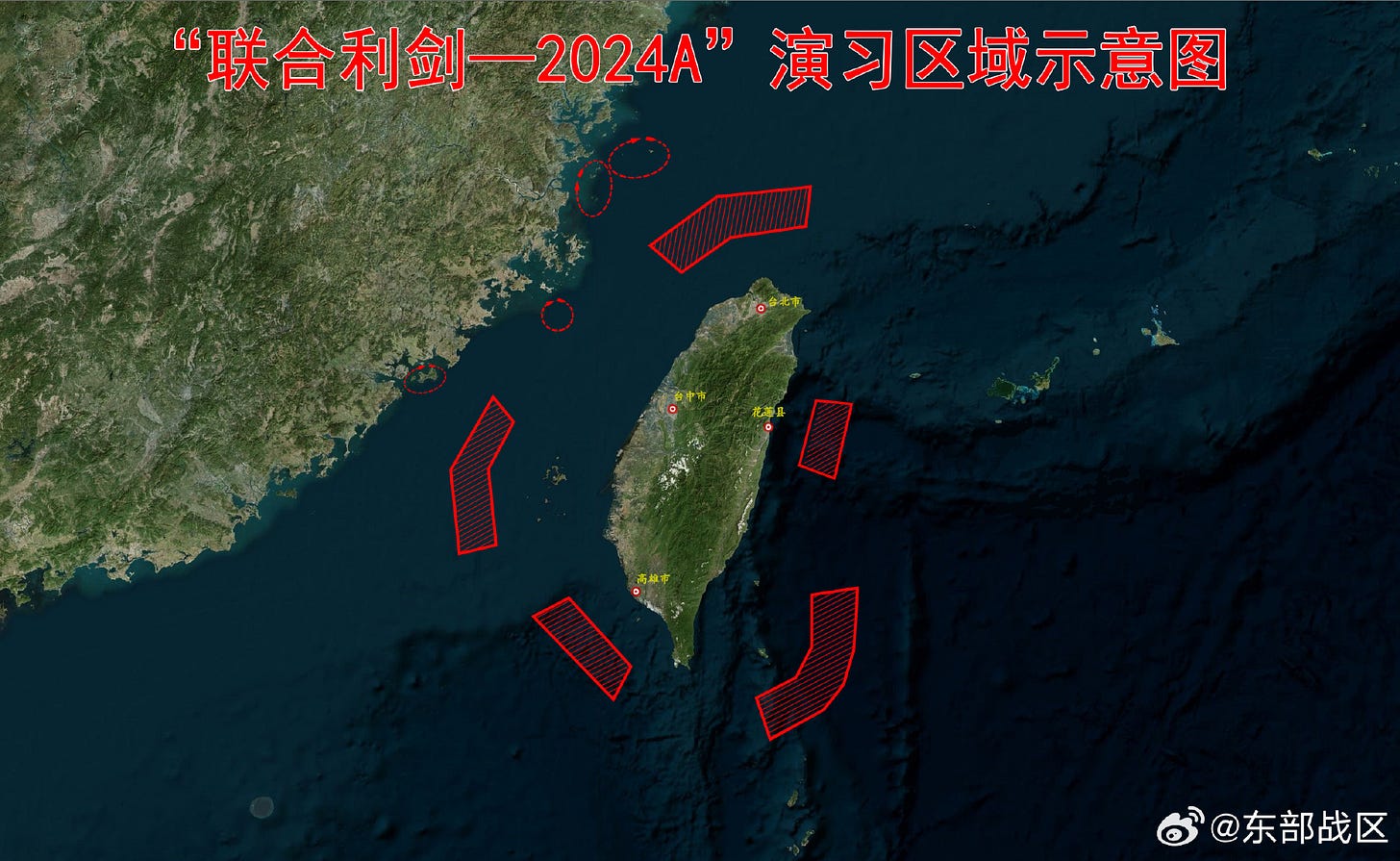

Implications for the Taiwan Strait

For Taipei and Washington, the command vacuum raises acute questions. A PLA led by untested loyalists — lacking veterans like Zhang, who earned his stripes in the 1984 Battle of Laoshan against Vietnam — may exhibit less caution in crisis. Yet the purges also signal internal fragility: a military hollowed out at the top is less reliable for high-stakes operations like a Taiwan invasion. Xi’s emphasis on ‘frictionless obedience’ could accelerate timelines toward 2027 readiness, but it risks miscalculation born of echo-chamber certainty rather than grounded assessment.6

The Silicon Curtain and Global Dependencies

This internal decapitation suggests that Beijing is shifting its primary focus toward a wartime preparation economy. We are seeing a pivot away from the old infrastructure-led growth toward a modernized industrial system designed for resilience under siege. China is doubling down on grid-management and digital social control, preparing its domestic population for the material hardships and isolation that would accompany a major conflict. This means the Chinese economy is no longer being managed for consumer prosperity or global integration. It is being hardened. For the global market, this implies a permanent state of supply chain de-risking as Beijing treats its industrial capacity as a strategic arsenal rather than a commercial engine.

The core of this industrial hardening is the semiconductor supply chain, where the battle lines have solidified into what analysts now call the Silicon Curtain. China has successfully localized over 35 percent of its semiconductor equipment through its Big Fund Phase 3, allowing firms like SMIC to scale 5nm production despite severe Western lithography restrictions. More critically, Beijing is racing to weaponize the legacy chip market, which involves the workhorse semiconductors at 28nm and above that power everything from engine control units in cars to household appliances and critical infrastructure. The global legacy chip market is projected to reach 284.3 billion dollars in 2026, and China’s aggressive expansion in this sector is a strategic move to create global dependency. By flooding the world with state-subsidized, low-cost mature nodes, Beijing is attempting to create a chokepoint where Western industries cannot function without Chinese-made silicon.7

The January 14, 2026, U.S. tariffs of 25% on AI-critical semiconductors underscore Washington’s sliding-scale containment: choke advanced nodes while allowing (and subsidizing) legacy diversification elsewhere. Meanwhile, China’s Big Fund Phase III continues pouring resources into mature nodes, aiming to make global industries — from automotive to consumer electronics — subtly dependent on Beijing-controlled supply.8

The Western response has been equally decisive. The U.S. has introduced tariffs of up to 145 percent on a range of Chinese semiconductor imports, while the EU’s Chips Act aims to double Europe’s market share to 20 percent by 2030 to mitigate reliance on external sources. On January 14, 2026, the United States further escalated by setting 25 percent tariffs on specific semiconductors critical to AI. This two-pronged squeeze strategy leverages Western dominance in electronic design automation and advanced packaging, such as TSMC’s CoWoS technology, to maintain a sliding scale of control over China’s AI capabilities while reshoring backend processes to North American soil. The goal is an All-American high-performance chip ecosystem free from foreign surveillance or backdoor vulnerabilities.

The Trump-Xi Summit in April

The impending Trump-Xi summit in early April 2026—Trump’s visit to Beijing, the first of potentially multiple high-level meetings this year—offers a stark diplomatic counterpoint to Beijing’s internal hardening. Following a February phone call where the leaders discussed trade, Taiwan, and global issues, the meeting aims to extend the fragile October 2025 trade truce (possibly by up to a year) and secure deliverables like agricultural/energy deals to burnish optics ahead of U.S. midterms.9 In a gesture of temporary détente, the Trump administration has paused key tech curbs—such as bans on China Telecom operations and restrictions on Chinese equipment for U.S. data centers—ahead of the talks, though officials note these could be revived if relations sour.10 This transactional maneuvering underscores Beijing’s asymmetric position: even as Xi consolidates absolute control domestically and prepares for siege-like resilience, he retains leverage in bilateral bargaining, using short-term concessions to buy time for long-term strategic autonomy.

From Developmental to Mobilization State

What the purge of Zhang Youxia ultimately reveals is not only a reconfiguration of military authority but a deeper transformation of China’s political economy itself.

For four decades, the Chinese Communist Party derived legitimacy from a developmental bargain of rapid growth, rising living standards, and integration into the global economy in exchange for political acquiescence. That bargain now appears to have been replaced by something far more austere, a mobilization model in which security, resilience, and ideological discipline supersede prosperity as the primary sources of stability. This is the shift from a developmental state to a mobilization state. In such a system, capital is no longer allocated to maximize efficiency or innovation but to ensure survivability under conditions of sanctions, blockade, and conflict. Redundancy becomes policy and overcapacity becomes insurance. Subsidizing legacy semiconductor fabs, duplicating supply chains, and stockpiling industrial inputs would be irrational in peacetime economics but entirely rational if war is treated as a structural condition rather than a contingency.

❝ The economy is no longer only a platform for global integration but a reserve of national power.

This transformation also reorders the hierarchy between state and market. Private enterprise is no longer the engine of growth but a subcontractor to national strategy. Party committees inside firms, national tasking of production lines, and regulatory pressure that functions as silent expropriation all signal a downgrading of entrepreneurial autonomy. The purge of senior generals mirrors this logic in the military realm because experience and institutional memory are being traded for frictionless obedience. Loyalty now outweighs competence as the organizing principle of both command and capital.

A mobilization economy requires financial repression. Household savings are increasingly redirected toward strategic sectors like defense industries, semiconductors, rare earth processing, digital surveillance, and social control infrastructure. This accelerates trends already visible in China’s stagnating consumer recovery. Youth unemployment, property deflation, and declining household confidence are not temporary cyclical problems but structural features of an economy that now privileges security over welfare. The result is a narrowing of the social contract. Consumption gives way to extraction, inequality widens between state-linked firms and the rest of society, and welfare is subordinated to preparedness. Historically, such systems resemble late-imperial or late-Soviet political economies that are inwardly coercive, outwardly assertive, and increasingly dependent on nationalism to justify material sacrifice.

This shift also undermines Beijing’s ambition to internationalize the renminbi and expand financial influence. One cannot build a trusted global currency while preparing for autarky. Investors will price in capital controls, sanction risk, and political unpredictability. Paradoxically, the more China prepares for war, the less financial power it possesses to deter it. Strategic hardening trades economic leverage for political insulation. China’s semiconductor strategy illustrates this logic of asymmetric re-coupling: autonomy inward, dependence outward. By flooding global markets with subsidized mature-node semiconductors, Beijing seeks to embed leverage where it is least visible and hardest to unwind. Yet this strategy carries its own risks. Evidence already suggests that such dumping provokes diversification rather than dependence. India, Vietnam, and Mexico are absorbing backend manufacturing, and Western governments are subsidizing redundant fabs. Firms are redesigning products to avoid Chinese inputs, leading not to global reliance but to hardened trade blocs and permanent friction.

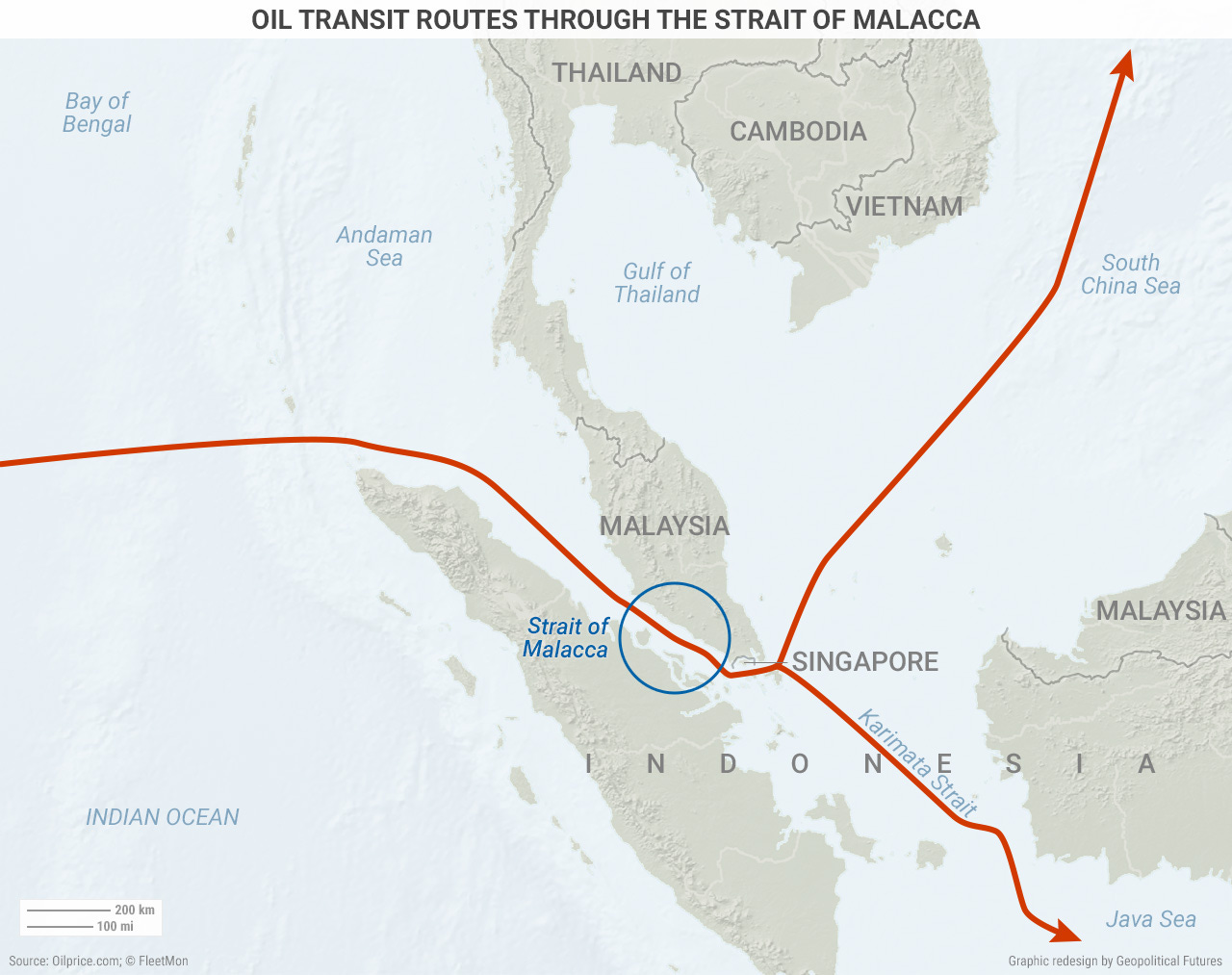

The Malacca Dilemma in a Mobilization Context

This transition to a mobilization state has profound implications for global energy corridors, specifically regarding the Malacca Strait. Beijing’s long-standing Malacca Dilemma, where 80 percent of its oil imports pass through a chokepoint it does not control, has shifted from a theoretical vulnerability to a high-priority operational target. In a mobilization state, China’s energy strategy now prioritizes land-based alternatives and “sanction-proof” maritime transit. We are seeing a massive surge in the use of dark ships and shadow fleets to bypass Western monitoring, alongside a rapid acceleration of overland corridors through Pakistan and Myanmar that seek to circumvent the strait entirely. While these land routes currently handle less than 10 percent of China’s 15 million barrels per day consumption, the goal is not total replacement but the creation of a survival-tier baseline. For the global community, this means the Malacca Strait is no longer just a trade artery but a contested maritime front where Beijing’s “Far Seas Protection” doctrine will increasingly challenge international transit norms to secure its strategic lifeline.11

Recent satellite tracking shows a surge in shadow fleet usage, with uninsured tankers rerouting via alternative paths. While land corridors (e.g., China-Myanmar, China-Pakistan) remain limited, Beijing’s push for ‘sanction-proof’ baselines signals preparation for blockade scenarios, elevating the Malacca Strait from chokepoint to flashpoint.

The fall of Zhang Youxia sends a message not only to generals but to bankers, bureaucrats, and CEOs: dissent is risk and conformity is survival. This has predictable consequences. Officials will underreport problems, resources will flow toward politically safe sectors, and innovation will become ritualized, measured in slogans and statistics rather than breakthroughs. Corruption will not disappear but will mutate into factional control of strategic assets. This creates a state of strategic hallucination where leaders begin to mistake production figures for readiness and obedience for effectiveness. A command economy governed by loyalty metrics will increasingly believe its own propaganda. Historically, wars are rarely launched from confidence alone; they are launched from false confidence generated by bureaucratic echo chambers.

❝ The silence in Beijing’s military ranks should not be mistaken for stability.

Without senior generals shaped by real combat experience to provide friction and caution, strategic decision-making becomes narrower, faster, and more ideological. The danger is not recklessness but certainty. Even if this trajectory is born of fear rather than ambition, it locks China into a fortress political economy defined by slower growth, higher state control, permanent confrontation pricing, and ideological justification for hardship. Historically, such systems face only two exits: escalation to legitimize sacrifice or stagnation that corrodes legitimacy from within.

From Developmental State to Security State: Implications for Global Stability

The purge of Zhang Youxia marks the crossing of a threshold in China’s political economy from reform logic to wartime logic. Capital allocation, industrial policy, and social governance are now instruments of strategic preparation. The economy is no longer a platform for global integration but a reserve of national power. More precisely, the battlefield has entered the economy. Through supply chains, finance, and digital governance, conflict has been internalized into the structure of everyday production. In such a system, miscalculation is not an accident; it is a design risk. The silence after the storm inside the PLA should not be mistaken for stability. It is the quiet of a machine being tuned for a single purpose.

The West must recalibrate: engagement with a mobilization-state China is engagement with a system wired for confrontation. Deterrence now requires not just military balancing but economic resilience — diversifying supply chains, hardening alliances, and preparing for prolonged friction. The silence in Beijing’s military ranks is not calm; it is the sound of gears turning toward an uncertain, high-stakes future.

About the Author:

Eric Huang

Eric Huang. is an expert in US-China-Taiwan geopolitics, strategic planning, and crisis communication. He works at the intersection of policy and technology, helping organizations anticipate risks and seize op…

📍Taipei and Washington

Footnotes

China investigating top general over serious violations, Reuters, Jan 26, 2026.

Zhang Youxia: Purge of China’s top general leaves military in crisis, Stephen McDonell, BBC, Jan 26, 2026.

Zhang Youxia’s Differences with Xi Jinping Led to His Purge, K. Tristan Tang, Jamestown Foundation, Jan 26, 2026.

China’s Military Reforms Since 2015: Is Time on Its Side?, Dennis J. Blasko , The Diplomat, Dec 29, 2025

Mission Command with Chinese Characteristics? Exploring Chinese Military Thinking About Command and Control in Future Warfare, Nathan Beauchamp-Mustafaga, Ivana Ke, Amanda Kerrigan, and Edmund J. Burke, RAND Corporation, Oct 22, 2025.

Xi’s military purges will make him wary of invading Taiwan, Phillip C. Saunders, Lowy Institute, Feb 5, 2026.

China sets up third fund with $47.5 bln to boost semiconductor sector, Reuters, May 27, 2024.

President Donald J. Trump Takes Action on Certain Advanced Computing Chips, White House Fact Sheet, Jan 14, 2026.

China confirms it is talking to US about Trump visit as trade truce stays on the cards, Khushboo Razdan, Xinmei Shen, Dewey Sim and Mark Magnier, South China Morning Post, Feb 12, 2026.

Exclusive: Trump pauses China tech bans ahead of Xi summit, Alexandra Alper, Reuters, Feb 12, 2026.

Malaysian waters see return of oil transfer by ‘dark fleet’ of tankers, Ushar Daniele, South China Morning Post, Feb 4, 2026.