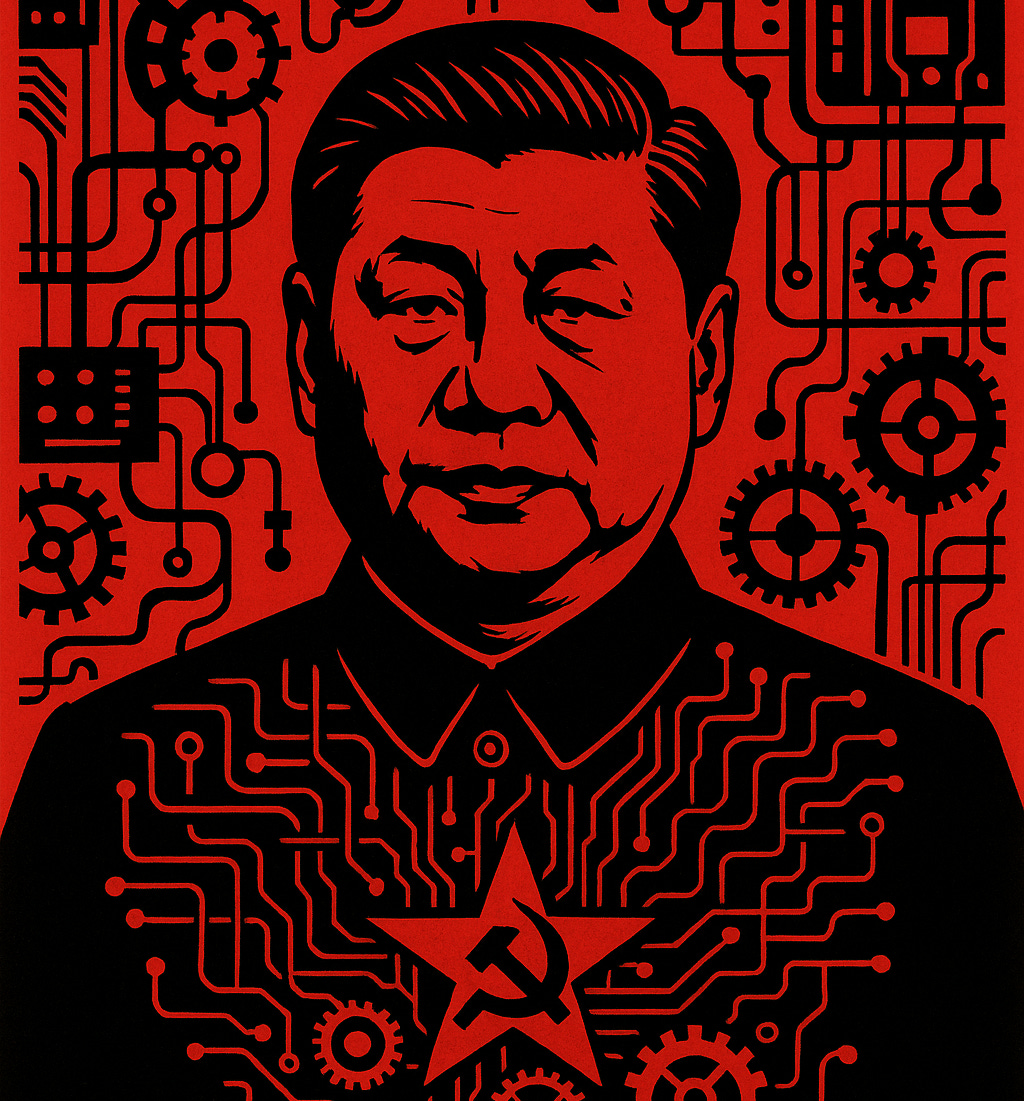

Xi Jinping: The Living Heart of the Party

The CCP has become internalized within its leader — will it outlive him?

Xi has not dismantled the party. He has absorbed it.

Introduction: The Perils of Centralization

Editor-in-Chief Lyric Hughes Hale’s twin essays, Who Will Succeed Xi? and Xi’s Wobble provide some of the most insightful recent portraits of China’s power structure. She describes a regime that stands upright only because Xi Jinping holds it steady, like a chair balanced precariously on one leg.

This essay by Eric Huang extends Hale’s thesis: the question of what comes after Xi is not about who follows, but whether the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) can reinvent itself once personal rule replaces institutional succession. The CCP’s most stable era may also be its most fragile.

Absorbing the Party

Xi has not dismantled the Party; he has absorbed it. The collective leadership model that once provided predictable rotation of power has been replaced by a system defined by personal loyalty, bureaucratic gatekeeping, and a pervasive culture of caution. What looks stable from the outside is actually a mechanism of constant tension management.

In Foreign Affairs, Tyler Jost and Daniel Mattingly argue that China is entering a dangerous political phase defined by the uncertainty of succession. They emphasize the enduring importance of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) as an implicit kingmaker and point to the rising visibility of Chen Jining, the Shanghai Party Secretary and former Tsinghua University president. Chen, a scientist-turned-politician with a background in environmental policy, represents the technocratic archetype once celebrated as China’s reformist future.1

The Rise of Technocrats—and the Fall of Reformers

Yet Chen’s rise also exposes a broader shift. The once-visible group of Harvard Kennedy School or Oxford-educated “party scholar” cadres who blended Western public policy training with CCP discipline has shrunk dramatically since Xi consolidated power. The share of senior officials with Western postgraduate experience has fallen sharply, replaced by domestically trained technocrats with closer ties to security institutions and ideological commissions. Xi’s China now prizes internal pedigree over international polish.

Chen is not a liberal reformer in the Western sense. His profile illustrates how Xi’s system has redefined meritocracy: competence is still valued, but only when coupled with absolute political reliability. The technocratic elite of today are engineers of control rather than architects of reform.

There are no successors—only custodians waiting for instructions.

The End of Institutional Succession

The old succession formula of two terms, ten years, and a designated heir groomed in advance no longer exists. Xi’s 2018 constitutional change removed term limits, but the deeper transformation is cultural.

In the past, a would-be successor would spend years being carefully groomed: serving as a provincial Party secretary, then as a vice premier or PSC member, building relationships within the Central Committee and the PLA. These milestones provided the institutional legitimacy necessary to inherit power.

Under Xi, that apprenticeship pathway has been severed. The expectation of turnover has vanished. The Politburo Standing Committee no longer functions as a training ground for successors; instead, real power flows through the General Office, the Secretariat, and the Central Commissions directly chaired by Xi. In this environment, loyalty is safer than innovation; ambition is expressed through compliance.

A Technocratic Elite

The system has not collapsed into chaos. Rather, it has been redesigned for indefinite continuity. It operates less like a party-state and more like a continuously calibrated command structure. There are no successors—only custodians waiting for instructions.

Recent data on the 20th Central Committee’s civilian members reveals a strikingly technocratic profile: nearly half (46.8%) hold doctoral degrees, 38.7% master’s degrees, and only 12.9% bachelor’s degrees—the most academically credentialed elite in CCP history. 2

Their expertise, however, is concentrated: about 45% trained in science and engineering, 14% in economics and management, and 15% in humanities or philosophy. Only 6% studied law or political science.3

Regional representation also tells its own story. Eastern provinces account for 43% of Central Committee members, far exceeding their 26.8% share of the national population. 4This coastal overrepresentation reflects both the historical weight of reform regions and Xi’s preference for cadres from growth centers like Shanghai, Zhejiang, and Jiangsu.

The CCP has evolved into a party of engineers and administrators. Political loyalty is assumed, technical skill mandatory, and ideological diversity has all but vanished. The retreat of foreign-trained policymakers signals the end of an era when Chinese officials acted as intellectual intermediaries between Beijing and the West.

The Secretariat State

Xi’s governance model depends on what Chinese observers call mishu wenhua (秘书文化)—“secretarial culture.” Power resides not in ministers or governors but in gatekeepers who control information flow to the top.

Cai Qi, Xi’s longtime ally and now chief of staff, epitomizes this structure. Around him stands a circle of trusted aides—the mishu bang (秘书帮), or “secretariat faction”—a bureaucratic ecosystem sustained by loyalty and discretion rather than factional balance or ideological debate.

Among them, Li Qiang, the premier and Xi’s former chief of staff in Zhejiang, demonstrates how administrative trust now outweighs institutional seniority. His loyalty during Shanghai’s 2022 lockdown earned him promotion despite public criticism, underscoring that faithful execution of orders counts more than performance or popularity.

Ding Xuexiang, the executive vice premier and former director of the General Office, represents the archetype of the “good secretary”: silent, discreet, and indispensable. Known in Zhongnanhai as Xi’s “shadow,” he has mastered coordination and message discipline, exercising power through proximity rather than visibility.

Other figures complete this inner secretariat: Cai Qi, the ideological gatekeeper; Chen Min’er, the propagandist shaping narrative; He Lifeng, the economic interpreter of Xi’s will; and Chen Yixin, the Ministry of State Security chief enforcing political control.

Each rose not through factional maneuvering but through administrative service, acting less as policymakers than as executors of Xi’s intent.

Together they illustrate how personal loyalty and bureaucratic precision have replaced collective leadership and policy debate as the true currency of power.

The Costs of Control

This system enforces ideological discipline and minimizes surprises. It also isolates Xi from dissent and weakens feedback loops. The state hears its leader too loudly—and the outside world too faintly. The result is remarkable stability paired with growing cognitive rigidity: an empire of management without debate.

At seventy-two, Xi shows no sign of political decline and could easily serve another term, extending his rule into the 2030s. His most likely successors, should he designate one, will be technocratic loyalists rather than princelings with independent bases. The tension between “red-blood” revolutionaries and “blue-blood” technocrats now defines elite politics.

Xi’s solution has been to merge the two: ideological principals commanding technocratic deputies.

Asymmetric Opacity: Implications for the West

Some observers compare China’s evolution to Taiwan’s Kuomintang trajectory: strongman rule followed by technocratic stabilization and eventual pluralization. The analogy is misleading. China lacks external protection, faces economic stagnation, and remains structurally securitized. The CCP’s control mechanisms make gradual liberalization improbable, though procedural adaptation remains possible. The future is less democratic evolution than bureaucratic endurance.

For US-China relations, the meaning of Xi’s political architecture is not procedural but structural. Washington now confronts a system that sustains itself through one man rather than one set of institutions. This changes the logic of engagement: China’s foreign policy is no longer institutionalized diplomacy but personalized continuity.

When authority is concentrated and communication flows upward through layers of gatekeepers, foreign policy becomes cautious, reactive, and prone to paralysis. Bureaucrats avoid initiative without explicit approval, even when coordination is urgently needed. Strategic signaling from Beijing may therefore lag events, making it harder for Washington to interpret intent or escalation risk.

Meanwhile, the contraction of Western-educated officials has removed a generation of informal intermediaries who once translated between Chinese and global norms. The result is an epistemic gap that widens every time Beijing’s bureaucracy chooses caution over clarity.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to econVue to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.